4 December 2025

By Stephen Gowans

Canada has shelled out $22-billion of taxpayer money on assistance to Ukraine since Russia invaded the country in February, 2022. [1] Might our money have been better spent on other matters?

For example, 20 percent of Canadian adults do not have a family doctor. [2] Could this money have been used to help provide Canadians with access to physicians and nurse practitioners?

“Affordable housing,” according to The Globe and Mail, “is out of reach everywhere in Canada.” [3] Could Ottawa’s generous aid to Ukraine have been spent instead on helping to solve Canada’s housing and rental crisis?

Ottawa plans to cut over 11 percent of the federal public service, a move which, on top of increasing the jobless rate—already near 7 percent—will likely mean longer wait times for unemployment benefits, passports, and government assistance programs. [4] Might future outlays slated for aid to Ukraine be better spent on maintaining public services for Canadians?

According to the government’s own statistics agency, “Over one in four Canadians live in a household experiencing financial difficulties.” [5] Could $22 billion have helped relieve these Canadians of their financial burdens?

Prime Minister Mark Carney says that “Canada will always stand in solidarity with Ukraine.” [6] In practice, helping Ukraine means doing less for Canadians. It means poorer public services, under-funded health care, less affordable housing, and more economic insecurity. Carney doesn’t say why Canadians must make sacrifices to stand with Ukraine, but knowing why is important if pressing domestic needs are to be ignored. Is the diversion of funds that could be used to meet Canadians’ needs justified?

To answer that question, we must first understand why Ottawa is backing Ukraine. The answer has a lot to do with Canada’s place in the informal US empire.

Canada is part of a US-led alliance that regards Russia as a “revisionist” power—that is, as a country which challenges the US-led world order—an order which naturally puts the United States at the top. The war in Ukraine is a contest between Washington, on one side, and Moscow, on the other. Russia is one of two states (along with China) powerful enough to challenge US ‘leadership’, or, to put it less euphemistically, US tyranny. While the word tyranny seems harsh, what else would one call a US-led global defined by Washington to, by its own admission, put US interests above all others? [7] Napoleon’s order in Europe was summed up by the watchword France avant tout, while Nazi Germany sought to create an order in Europe defined by the phrase Deutschland uber alles. Implicitly, Washington predicates its own global order on the idea of the United States above all others, or, America First.

Russia, Washington says, wants to revise the US-led world order. There’s no question that Moscow wants to do this. It has no intention of acquiescing to the will of Washington, and because it’s strong enough—unlike most other states—to challenge US primacy, it resists integration into the informal US empire. Russia prefers to carve out its own empire, where its own billionaires exercise influence and monopolize profit-making opportunities. The war is, thus, au fond, a contest over which country’s billionaires will get to exploit the profit-making opportunities Ukraine has to offer—the United States’ or Russia’s?

On a broader level, the war is being fought—with Ukraine as the tip of the US spear, or proxy—over the question of who will dominate parts of Eastern Europe that have historically fallen under Russian, or Soviet, domination. Will it be Russia or the United States? Ukraine, being the largest and most significant part of the contested territory, is the cockpit of the current struggle. The prize for the winner is lucrative investment opportunities and strategic territory, vital to the questions of a) whether the United States will continue to lead a world order as rex, and b) whether Russia will successfully resist US efforts to make it bow to US pre-eminence.

In disbursing $22 billion to the US side of the contest, instead of using the funds to improve the lives of Canadians at home, Ottawa is playing a vassal role to US investor and corporate interests and aiding, what in the end, is a project of furnishing US billionaires with investment opportunities at the expense of Russian magnates.

Defenders of Ottawa’s decision to aid Ukraine will point to a moral obligation on the part of Canadians to defend a victim of illegal aggression. To be sure, the Russian invasion of Ukraine is both a contravention of international law and an aggression.

However, Canada does not aid all, or even many, countries that fall prey to the aggression of imperialist marauders. If it did, it would soon fall out with its patron, the United States, the world’s imperialist marauder par excellence. If Ottawa genuinely stands with the victims of aggression as a matter of principle, it would have funneled military and other aid to Iran (only recently the target of a blatant and flagrantly unlawful US-Israeli aggression); to Syria, when Washington was bankrolling Al-Qaeda to bring down the Arab nationalist state (which it did do, successfully); to Cuba, the victim of a cruel six-decade-long campaign of US economic warfare aimed at ensuring that an alternative to the capitalist order will never thrive; to Venezuela today, the target of a US military pressure campaign whose object is to install a puppet regime in Caracas to better loot the country’s land, labor, and resources, especially its oil; and on and on, ad nauseum. Need I mention Korea, Vietnam, Granada, Panama, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya?

Which brings us to the Palestinians. If the Canadian government was really motivated to defend the victims of expansionary rogue regimes that flagrantly violate international law, it would have provided aid to the Palestinian national liberation movement long ago. Palestinians are the principal victims of Israel, a notorious practitioner of rapine, aggression, territorial expansion, and contempt for the UN Charter. Instead, Canada has faithfully assisted the Zionist state to carry out what the United Nations, countless human rights organizations, and top genocide scholars, have called a genocide. Ottawa has sent arms to Israel; banned Canadians from sending aid to Palestinians standing up to the aggression and demonized Palestinian freedom fighters as terrorists; lavished diplomatic support on the Zionist state; and has refused to take meaningful action to pressure Tel Aviv to abide by the countless UN resolutions directing Israel to end its illegal occupations of the West Bank, Gaza, East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights.

So, no, Ottawa isn’t sending billions of dollars to Kyiv because it deplores aggression, champions international law, and feels morally bound to stand with the victims of Russian imperialism. To believe this is to close one’s eyes to Canada’s record as faithful backer of US and Israeli imperial aggressions. The reality is that Canada is furnishing Kyiv with generous aid because Ottawa’s standard operating procedure is to support—or at the very least, not get in the way of—the foreign policy preferences of its US master. If backing Washington and its proxies in West Asia (Israel) and Eastern Europe (Ukraine) means skimping on satisfying the needs of ordinary Canadians, then, from Ottawa’s perspective, so be it.

While this is bad enough, it’s about to get much worse. Ottawa has committed, along with other NATO countries, to significantly increasing its military spending to five percent of GDP from a little over one percent today. This is part of a Pentagon strategy to shift responsibility for confronting Russia from the United States to Washington’s NATO subalterns, so the US military can either turn its full attention to intimidating China [8], by one plan, favored by so-called prioritizers in the US state, or concentrate on shoring up US hegemony in the Western Hemisphere, advocated by so-called restrainers [9].

The problem here is that there is no compelling rationale to increase military spending almost five-fold. The ostensible reason for the increase is to ‘deter’ Russia from further aggression in Europe. But no serious observer believes Russia is able to take on NATO, even at NATO’s allegedly paltry current levels of spending. Recently, The Wall Street Journal reported that “A senior NATO official said Russia doesn’t have the troop numbers or military capability to defeat the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in Europe.” [10]

The idea that the United States carries the burden of defending Europe and that Europe could not defend itself without US assistance—and that therefore Washington’s NATO subalterns must significantly boost their military outlays—is false. In point of fact, the United States contributes much less to the defense of Europe than Europe does itself. Table 1 shows that the United States spends $50 billion annually on military operations in Europe, overshadowed by the $476 billion that Europe’s NATO members spend yearly. Whereas 100,000 US troops serve in Europe, the alliance’s European members contribute over 2 million infantry, air crew, and sailors to the continent’s defense.

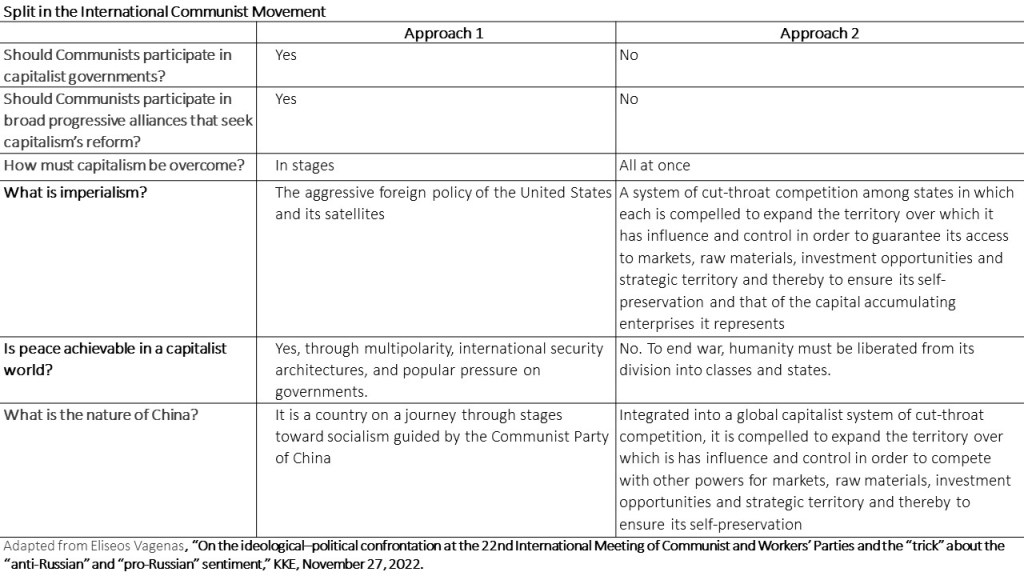

| Table 1. Russia vs. NATO in Europe | ||

| Military spending ($B) | Military personnel | |

| Russia | $142 | 1,200,000 |

| European NATO members | $476 | 2,041,300 |

| US contribution to Europe | $50 | 100,000 |

| European NATO members + US contribution | $526 | 2,141,300 |

| (Europe + US contribution) / Russia | 3.7 | 1.8 |

| Sources: Russian military spending: Robyn Dixon, “Russian economy overheating, but still powering the war against Ukraine,” The Washington Post, October 27, 2024. Russian military personnel: CIA World Factbook. NATO military expenditures and personnel: “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2024)” NATO. March 2024. US military spending in Europe: Steven Erlanger, “NATO Wants a Cordial Summit, but Trump or Zelensky Could Disrupt It,” The New York Times, May 26, 2025. US military personnel: Daniel Michaels, Nancy A. Youssef and Alexander Ward, “Trump’s Turn to Russia Spooks U.S. Allies Who Fear a Weakened NATO,” The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 20, 2025. | ||

What’s more, together, NATO’s European members spend over three times as much on their militaries as Russia does on its armed forces, while the number of NATO personnel in Europe, excluding the US contribution, is almost double Russia’s (Table 2). Were Europe’s NATO members to meet Trump’s five percent target, they would exceed Russia’s military spending by a factor of eight. To be sure, this would deter a Russian offensive in Europe, but it would be overkill. When the idea of the five percent target was first broached by the incoming Trump administration, former U.S. Ambassador to NATO Ivo Daalder dismissed it as “a made-up number with no basis in reality.” He said that “European NATO members now spend three times as much as Russia does on defense, and at five percent Europe would outspend Russia by $750 billion annually, spending roughly 10 times what Russia spends.” [11] Daalder’s numbers and those of Table 2, while differing slightly in some respects, point to the same conclusion: the five percent target is far too high.

| Table 2. Russia vs. NATO (European members) | |||

| Russia | European NATO members | Europe / Russia | |

| Population | 143,800,000 | 592,872,386 | 4.1 |

| GDP ($B) | $2,021 | $23,023 | 11.4 |

| Military spending ($B) | |||

| At current levels | $142 | $476 | 3.4 |

| At 5% of GDP (NATO) | $1,151 | 8.1 | |

| Military personnel | 1,200,000 | 2,041,300 | 1.7 |

| Sources: NATO population: CIA World Factbook. NATO GDP, military expenditures, and personnel: “Defence Expenditure of NATO Countries (2014–2024)” NATO. March 2024. Russian military spending: Robyn Dixon, “Russian economy overheating, but still powering the war against Ukraine,” The Washington Post, October 27, 2024. Russian military personnel: CIA World Factbook. Russian population and GDP: World Bank. | |||

Russia is militarily incapable of territorial expansion beyond Ukraine, and even in Ukraine—a country with only one-quarter of Russia’s population—its capabilities are severely tested. Russia is no match for an alliance, whose European members alone, have four times its population and over 11 times its GDP. The idea that Russia has the capability to invade a NATO-alliance member is—to use a favorite phrase of US international relations specialist John Mearsheimer—“not a serious argument.”

Despite these realities, various NATO governments, Canada among them, are trying to foster the illusion that Russia threatens Europe. They are doing so in order to manufacture consent for a stepped-up level of military spending that is far in excess of what is necessary to defend the continent from a Russian invasion. Not only is military spending at this level unnecessary, it will harm the interests of the vast majority of Europeans and Canadians. Higher defense spending will almost certainly mean cuts to public services. During a visit to Britain, the NATO secretary general warned British citizens that if they chose to funnel public-spending into maintaining the National Health Service and other public services, rather than meeting Trump’s arbitrary five percent target, they had “better learn to speak Russian.” [12] The message is clear: Important pubic services that benefit most of us, must be sacrificed in order to squander public funds on the military to meet a spurious threat. “Ramping up to 5 percent would necessitate politically painful trade-offs”, warns the New York Times. [13] Painful trade-offs mean painful for all but business owners and the wealthy. Within the current climate, the idea that higher military outlays will be underwritten by higher taxes on the rich and big business is unthinkable. Instead, the formula is: gull the public into believing a Russian offensive is imminent so they’ll accede to the gutting of public services.

Why would NATO countries commit to spending far more than necessary? There are three reasons that suggest themselves as hypotheses.

- The expenditures are intended for offense rather than defense. You don’t spend 8 to 10 times as much as your rival on weapons and troops to defend yourself. Doing so would be wasteful. But you do vastly outspend your rival if your intentions are intimidation and aggression, or your aim is to arms-race your opponent into bankruptcy and submission.

- Punishingly high military expenditures offer a pretext for NATO governments to ween people off public services. Public services are increasingly starved of adequate funding, often to fund tax cuts for the wealthy and increases in military expenditures. That governments routinely make these trade-offs show that they favor the wealthy, who rely little, if at all, on public services, but benefit from tax cuts. The wealthy also benefit from robust military spending, inasmuch as it provides investment opportunities in arms industries and underwrites hard-power which can be used to defend investments and trade routes and exact trade and investment concessions around the world.

- Much of the increased spending will flow into the coffers of US weapons makers, to the greater profit of investors who have stakes in the arms industry, while improving the balance of US trade, a major Trump administration obsession. By diverting public funds from public services to US arms dealers, NATO’s non-US members are submitting to US economic coercion and arm-twisting in order to placate their master.

Given that the accelerated spending increases will almost certainly be financed by budget cuts to public services, Canadians will see their healthcare, education, and pensions suffer—even more than they already do—so US arms manufacturers can enjoy generous profits. Canadians, perhaps, should have expected no less for having recently elected as prime minister the former head of Brookfield, a leading global investment firm. But even if they hadn’t, Canada, like all other capitalist countries, is so thoroughly under the sway of the leading lights of the business community—as a result of the community’s lobbying and other direct efforts to influence the government and its policies, but also as a consequence of the power the community wields by virtue of its ownership and control of the economy—that it doesn’t matter who is prime minister. With or without Carney, the policy and direction of the government would be the same. The only way it is going to change is if the power of private business to dominate government and public policy is ended by bringing private industry and private investment under democratic control.

NATO governments are presenting their citizens with a spuriously inflated threat as a pretext to significantly increase military expenditures. We’re expected to believe that over 590 million Europeans are unable to defend themselves against 144 million Russians who, after almost four years, still can’t defeat 40 million Ukrainians. (Of course, a big reason they can’t defeat Ukraine is because they’re also fighting the United States and its NATO lackeys, Canada included, who furnish Ukraine with training, weapons, and intelligence.) We’re expected to believe that even though Europe’s NATO members spend three times as much on the military as Russia does, and have almost twice as many troops, that the alliance is vulnerable to a Russian invasion. These military spending increases—totally unnecessary for self-defense—will not come without a cost. Already, officials of various NATO governments have initiated a discourse on the necessity of making painful cuts to public services. The Russia threat is spurious—a stalking horse for advancing the sectoral interests of wealthy investors. If we allow this deception to stand and meekly submit to runaway militarism, all but the superrich—friends and class cohorts of the Trumps, the Carneys, the Merzs, the Macrons, and the Starmers—will pay a heavy price.

With one in five Canadians without a family doctor, one in four households in financial straits, 40,000 public servants on the chopping block, and the housing and rental markets in crisis, we are already paying a price. Unless we act now—by withdrawing from the war over Ukraine for billionaire profits, prioritizing the needs of Canadians, and bringing industry and investment decisions under democratic control—the price will grow larger still.

1. Steven Chase, “Canada buying $200-million in weapons for Ukraine from U.S. stockpile,” The Globe and Mail, 3 December 2025.

2. Tia Pham and Tara Kiran, “More than 6.5 million adults in Canada lack access to primary care,” Healthy Debate, 14 March 2023.

3. Steven Globerman, Joel Emes, and Austin Thompson “Affordable housing is out of reach everywhere in Canada,” the Globe and Mail, 2 December, 2025.

4. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FQHljrFMbfA&t=46s

5. Labour Force Survey, October 2025, Statistics Canada, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/251107/dq251107a-eng.htm

6. Bill Curry and Melissa Martin “Carney pledges support for Ukraine, unveils defence aid details at Independence Day visit,” The Globe and Mail August 24, 2025.

7. John McCain once wrote that “We are the chief architect and defender of an international order governed by rules derived from our political and economic values. We have grown vastly wealthier and more powerful under those rules.” John McCain, “John McCain: Why We Must Support Human Rights,” The New York Times, 8 May 2017.

8. Michael R. Gordon and Lara Seligman, “Pentagon Official at Center of Weapons Pause on Ukraine Wants U.S. to Focus on China,” The Wall Street Journal, 13 July 2025.

9. Yaroslav Trofimov, “A Newly Confident China Is Jockeying for More Global Clout as Trump Pulls Back, The Wall Street Journal, 2 December 2025.

10. Matthew Luxmoore and Robbie Gramer, “Marathon Russia-U.S. Meeting Yields No Ukraine Peace Deal”, The Wall Street Journal, 2 December 2025.

11. Daniel Michaels, “Trump’s NATO Vision Spells Trouble for the Alliance,” The Wall Street Journal, 8 January 2025.

12. Mark Landler, “NATO Chief Urges Members to Spend Far More on Military,” The New York Times, 9 June 2025.

13. Landler.