September 13, 2023

By Stephen Gowans

In his latest Berlin Bulletin the Leftist writer Victor Grossman describes “further splits in weak, divided peace and leftist movements around the world” as the byproduct of the war in Ukraine. If the war has, indeed, fragmented the Left (rather than simply exposed pre-existing divisions), Grossman lets us know on which side of the divide he can be found. Putin’s decision to invade Ukraine, the US expatriate insists, is “primarily motivated by the wish to defend Russia against encirclement, suffocation followed by subservience or dismemberment.” Brendan Simms made the case, explored in a post I wrote yesterday, that Hitler’s decision to invade Ukraine in 1941 was motivated by his wish to defend Germany against encirclement, and suffocation followed by subservience or dismemberment by the far stronger Anglo-American alliance. In other words, the proximal cause of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is precisely the same as the proximal cause of Hitler’s invasion of the same territory. Yet no Leftist, much less a communist, would have adduced this motivation as an apology for an act of aggression. Grossman, however, does.

Notwithstanding Grossman, the war in Ukraine has produced no split in the Left. It has simply exposed a rift that has existed at least as far back as the Second international, and indeed, was the reason for the organization’s dissolution. The split can be described as one of reform vs. revolution, or a disagreement about what the Left should do in times of war: Support one side against the other, or work to bring about the demise of the very system that gives rise to war?

The split can also be described as a disagreement over what causes war and therefore over how war can be brought to an end. One side says that wars are caused by belligerent states that have an inherent drive to war. To prevent these states from acting on their belligerent compulsion, popular opposition must be mobilized to act as a restraining hand.

Grossman is clearly on this side. Responsibility for the war in Ukraine falls squarely on the shoulders of the US state. He writes,

[M]ost of the violence in the world was a product of the intrigues, the aggression, the weapons managed and controlled by those powerful clusters who maintain such a tight control of congressmen and senators, half of them millionaires, of Supreme Court majorities, almost always of the White House, also of the Pentagon, CIA, NED, FBI and dozens of other institutions. It is they, a tiny number, less than 0.1%, whose wealth outweighs that of half the world’s population, but who can never be sated. They want to rule the whole world.

In Grossman’s view, it is not capitalism, or the nature of international system, that caused the war in Ukraine, but the US ruling class, which, uniquely, in his view, wants to rule the world. Apparently, neither the Russian or Chinese ruling classes are gripped by the same ambition.

This calls to mind an observation the classicist scholar Mary Beard made about the Romans: They were no more belligerent than their neighbors and no more voracious for the spoils of war. They operated, as did the states with whom they went to war, within a system of international relations in which disputes, usually traceable to the clashing economic ambitions of their ruling classes, were usually resolved by violence. Their belligerence and lust for booty was no different from that of rival states. The Romans, however, were just more successful.

The reality that the US ruling class has had more success than its Russian counterpart in projecting economic, political, military, and ideological power abroad does not explain why there is a war. Grossman might as well say that Muhammad Ali caused the violence of boxing because he was the most successful pugilist.

The opposing position, the classical Marxist view, locates the cause of war in the system of international relations within a capitalist world economy. The Bolsheviks Bukharin and Preobrazhensky developed a succinct summary of this position: Each “producer wants to entice away the others’ customers, to corner the market. This struggle assumes various forms: it begins with the competition between two factory owners; it ends in the world wherein capitalist States wrestle with one another for the world market.”

Yes, indeed, the US capitalist class wants to rule the whole world. But so too does the Russian and the Chinese.

At the core of the classical Marxist theory of war are two propositions:

- Capitalism incessantly drives states to seek expanded profit-making opportunities beyond their borders.

- In a world divided among states, where each competes against the other, war is inevitable.

This view was expressed in the resolution of the 1907 Stuttgart Congress of the Second International, which Lenin and Luxemburg took a hand in writing. “Wars between capitalist states are as a rule the consequence of their competition in the world market, for every state is eager to preserve its markets but also to conquer new ones.”

The theory follows naturally from Marx and Engel’s observation in the Communist Manifesto about the expansionary nature of capitalism. “It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere.” Significantly, all of capitalism’s nestling, settling, and connecting, has been orchestrated by states, each vying with the other.

The classical view was hardly new or unique to Lenin and Luxemburg. It was expressed at the Second International’s London Congress as early as 1896. “Under capitalism the chief causes of war are not religious or national differences but economic antagonisms.” In 1910, the Copenhagen Conference reiterated this view: “Modern wars are the result of capitalism, and particularly of rivalries of the capitalist classes of the different countries over the world market.”

The solutions to the problem of war differ between Grossman’s analysis of the cause of war and that of Lenin et al. If the causes of war are, as Lenin argued, the division of humanity into classes and nations, then the solution to war is to overcome the divisions which set humanity against itself, beginning with the socialist revolution. That’s why Lenin and his colleagues always maintained that the problem of war should be met, not by choosing sides in disputes between bourgeois states, but by overthrowing them all.

If, on the other hand, you believe that war is caused by bad actors following their bad urges, then the solution to war lies in pressuring bad actors to behave more congenially and erecting guardrails to prevent disputes from getting out of hand.

Here’s Grossman:

The world needs to drop a curtain on this confrontation, increasingly threatening in Ukraine, increasingly dangerous in East Asia. Regardless of differences it must be halted. … Such a cease fire and successful negotiations must be the world’s immediate and urgent goal. Ultimately it must face a deeper imperative; not only reining in the super-rich, super-powerful intriguers – but, as they are an outdated but constant source of danger and dismay, their total banning from the world stage.

There’s little substance here. Grossman’s endorsement of a cease fire and successful negotiations is nothing more than an expression of pious benevolence. Who doesn’t want a cease fire and successful negotiations? Everyone wants a resolution to the war—but on their own terms, which is the problem. Cease fires and negotiations, are, then, never ends in themselves, but means to ends, and wishing they weren’t, won’t make them so.

Grossman’s hope that the “super-rich and super-powerful intriguers,” i.e., the US ruling class, will be restrained, and then banned, is utopian nonsense. How will it be restrained, and then banned? By moral suasion? If it can be restrained, haven’t we the power to ban it? And why only the US ruling class? Brecht’s observation that the bitch that gave birth to fascism is still in heat, can be extended: the bitch that gave birth to war is still in heat, which is why wars, like the one in Ukraine, continue to happen. Grossman seems to think that the bitch only gives birth to American pups.

The split in the Left over the war in Ukraine is reflected in the world’s Communist parties. The European Communist Initiative, a grouping of European Communist and Workers parties, recently dissolved over differences related to the war in Ukraine, but the differences go much deeper than the war itself. The Greek Communist Party (KKE), which vigorously champions the classical Marxist position, objected to the positions taken by some member parties. In the party’s view:

Positions were expressed that limited imperialism to the USA and its foreign policy and disputed that each capitalist state participates in the imperialist system according to its economic, political and military power, in the context of uneven development.

A number of Parties sided with capitalist Russia in the imperialist war. They justified and supported the Russian leadership and the invasion of the Ukrainian territory by claiming that this war is anti-fascist, opposing the position that the war is imperialist, expresses acute capitalist rivalries and is waged for the control of markets and wealth-producing resources, for energy and transport routes, leading the peoples to the slaughterhouse of war.

Furthermore, some parties presented China as a socialist state, while capitalist relations of production have long prevailed in China and the exploitation of the working class and of man by man, which is the very definition of capitalism, is intensifying. Chinese monopolies are leading in the international market, exporting capital and commodities, while China and the USA are competing for supremacy in the capitalist system.

The split recapitulates a division within the Second International circa 1914—one which led to the creation of the Third International and the Communist parties to which the current internal communist movement is its nominal heir.

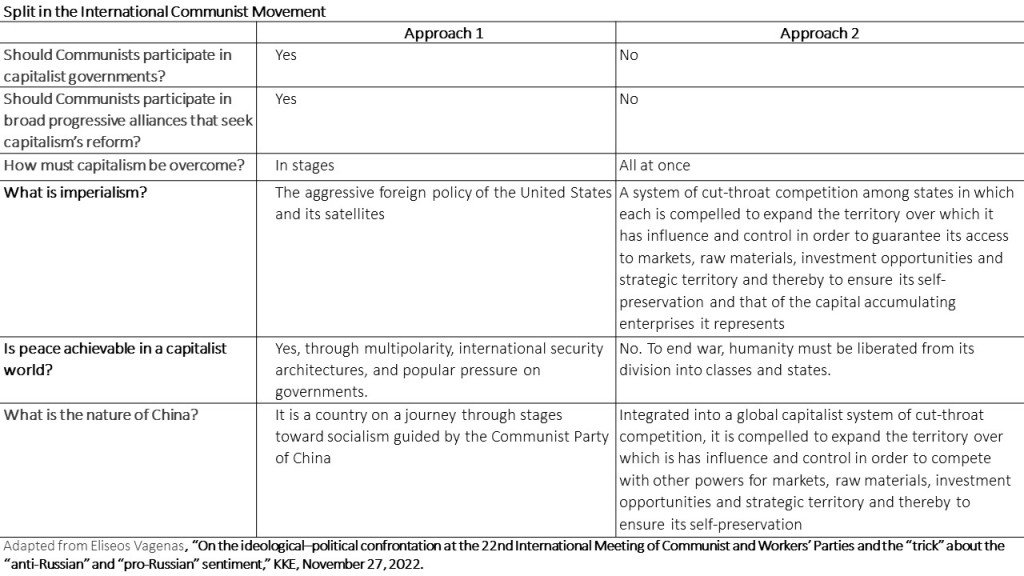

Last year, Eliseos Vagenas, a member of the KKE’s central committee, argued that the Russian invasion of Ukraine didn’t foster a split in the international communist movement; the split had existed long before the Russian invasion.

According to the Greek communist, communist parties had been split for some time on a least five questions, summarized below. When Russia invaded Ukraine, the parties moved to support or oppose Moscow, based on their pre-existing orientations, defined by either approach 1 or approach 2.

Two questions are critical to the positions the various ICM parties have taken on the war in Ukraine:

- What causes war?

- Is peace achievable in a capitalist world?

Communist parties that have either leaned toward outright support of Russia or greater condemnation of the United States and NATO, tend to view war in a manner that departs significantly from the classical Marxist view and have developed an understanding of how to end war that revises Marx and borrows from liberalism. These parties see war as developing from the aggressive foreign policy of one capitalist state, the United States (and its satellites), and regard Russia as a victim of a US drive to war. For them, the term ‘US imperialism’ is redundant, because imperialism is a monopoly of the United States.

What’s more, these parties tend to equate imperialism with war, and reject the notion that it has other dimensions, including peaceful capitalist competition, diplomacy, and even international security architectures. (Ask the North Koreans whether the UN Security Council is an expression of imperialism.) For these parties, imperialism is US war-making and little else.

In contrast, parties that view the war in Ukraine as an inter-imperialist conflict cleave to the classical Marxist view of imperialism. For them, imperialism is a system of cut-throat competition among states in which each is compelled to expand the territory over which it has influence and control in order to guarantee its access to markets, raw materials, investment opportunities and strategic territory and thereby to ensure its self-preservation and that of the capital accumulating enterprises it represents. The competition is expressed in multiple ways, including war, but not limited to it. It may be, and has more often than not been, expressed in trade and investment agreements. See, for example, Robinson’s and Gallagher’s The Imperialism of Free Trade.

Kenneth Waltz’s review of the split in the socialist movement precipitated by WWI, which he presents in his classic Man, The State, and War, calls to mind the current split in the international communist movement as identified by Vagenas.

Parties which support Russia in its war on Ukraine tend to embrace, as Waltz puts it, “the techniques of the bourgeois peace movement—arbitration, disarmament, open diplomacy” as well as the belief that popular opinion “can exert enough pressure upon national governments to ensure peace.” This, Waltz argues, is a revision of Marx’s view, which “points to capitalism as the devil.” The “socialism that would replace capitalism was for Marx the end of capitalism and the end of states,” and it was the end of states, for Marx, that meant the end of war. An anti-war movement founded on the notion that popular pressure and international security architectures can ensure peace, is a tradition that Waltz identifies as originating in the Second international as a revision of Marx.

Waltz elaborates: Members of the Second International “were united in that they agreed that war is bad, yet they differed on how socialists were to behave in a war situation. … Jean Jaures and Keir Hardie eloquently urged a positive program of immediate application. Socialists, they said, can force capitalist states to live at peace.”

In contrast, some “French and most German socialists argued that capitalist states are by their very nature wedded to the war system; the hope for the peace of the world is then to work for their early demise.” It is not, to bring the argument up to date, to support the weaker capitalist states in order to balance the strongest in a multipolar system. Indeed, this view is anti-Marxist in the extreme. For Marx, war ends when states end, not when weaker states balance the strongest and the world becomes multipolar.

The precursors of the Third International, Communists avant la lettre, argued that wars “are part and parcel of the nature of capitalism; they will cease only when the capitalist system declines, or when the sacrifices in men and money has become so great as a result of the increased magnitude of armaments that the people will rise in revolt against them and sweep capitalism out of existence.”

Compare this view with that of Vagenas, advocating for approach 2 as presented in the table above: The “capitalist world cannot be ‘democratized’.” It “cannot escape from wars no matter how many ‘poles’ it has.” War can only be escaped through “the struggle for the overthrow of capitalism, for the new, socialist society.”

Approach 1, then, looks very much like that embodied in the deeds of the Second International, while approach 2 resonates with that of the Third International (and the words of the Second). It is regrettable that some Communist parties have suffered an ideological drift toward positions that the founders of the international communist movement, Lenin and his colleagues, repudiated. Indeed, it can be said that there is no coherent international communist movement, except the one that comprises parties that have kept faith with Lenin’s view and have rallied around the KKE. As to the others, they have willingly become (to borrow Lenin’s phrase) playthings in the hands of belligerent powers and apologists for capitalism.

I agree that there are many socialist leaders (though not all) who act, not as champions of the working class, but as champions of one or more capitalist states, that there are many socialist leaders (though not all) who believe their task is to figure out which capitalist state to rally behind, and that there are many socialist leaders (though not all) who reflexively support whoever and whatever their own capitalist class opposes, including other capitalist states. Which means, as you say, that they let the capitalist class, either directly or indirectly, do their thinking for them.

I agree in one sense: The socialist movement is like a house that has been eaten away by termites inside the walls. It can get a nice new coat of paint, but the entire structure is rotten to the core. All it needs is just a slight trembler, a small earthquake, and the entire structure will come falling down. I have written regularly on that on my blog, oaklandsocialist.com, and I think the causes of the degeneration are too long and complex to write about here. Where we may disagree is this:

The leadership of the old socialist parties allowed their “own” capitalist class do their thinking for them, especially in a crisis situation. If their capitalists said “we must go to war with Germany,” or Britain, or whoever, then those “socialist” leaders parroted that. Today, it’s the mirror image of that. If “their” capitalists say “we must defend Ukraine”, then the modern day “socialists” say, “we must NOT defend Ukraine.” By feeling duty bound to opposing anything “their” capitalists say, they are STILL letting their capitalists do their thinking for them!

Your point that the left has long ignored globalization and its consequences for the working class is, I think, an important one. There is only one economy–the global one. One would think it would be Marxists, more than anyone else, who would appreciate the point and conduct their analyses accordingly. But the followers of Marx have resiled from Marx’s watchwords of “workers of the world unite” and “the working man has no country” in favor of viewing their own country and that of others in isolation, as if the close to 200 countries of the world were not inextricably interconnected and part of each other, and as if class struggle in one country is insulated from class struggle in another, as if, indeed, class struggle doesn’t ignore state boundaries and doesn’t happen on a world scale.

Analyzing the US and Chinese economies as if they are separate entities is absurd since the Chinese economy is every bit as much a part of the US economy as the US economy is part of the Chinese (while the EU economy is every bit as much a part of the US and Chinese economies as they are a part of its own, and so on.)

The bourgeoisie is keenly aware, as Marx was, that there is but one global economy, and uses this insight to its advantage. Nowadays, many people who call themselves Marxist-Leninists are more concerned with fighting their own bourgeoisie by expressing solidarity with the Chinese and Russian bourgeoisie, that is, by making themselves playthings in the hands of Moscow and Beijing, to borrow Lenin’s phrase, than in understanding the class struggle within the context of the only economy that matters: the global one.

There may be 195 countries in the world, but class struggle isn’t confined to 195 separate units, tightly contained within political boundaries called countries. It occurs on a global scale. Political boundaries may be superimposed on the struggle, and may affect it, but they don’t contain and circumscribe it. And yet, many Marxist-Leninists have unnecessarily, incorrectly, and disadvantageously used these artificial boundaries to set their horizons, express their allegiances, and carry out their work. Marxist-Leninists have but one horizon: the world; but one allegiance: to the international proletariat; and but one program of work: the emancipation of the global working class.

Those who proceed from the view that the Left should support other imperialists against U.S. imperialism have a strategic decision to make. How shall they to distort the principal contradiction in world imperialism today – the contradiction between the U.S. and the PRC? Shall they take

1) the broader multipolarity approach: Celebrate the rise of various capitalist countries in opposition to the U.S.

or

2) the “socialist China” approach: Insist that the monopoly capitalist PRC is actually socialist, and of course you must support one imperial power, excuse me, the socialist PRC, against the dominant and declining imperial power, the U.S.

In both camps, be sure to maintain the long tradition on the left of ignoring globalization and its consequences for the working class in the U.S. and in China.