Over two decades ago Vaclav Havel, the pampered scion of a wealthy Prague family, helped usher in a period of reaction, in which the holdings and estates of former landowners and captains of industry were restored to their previous owners, while unemployment, homelessness, and insecurity—abolished by the Reds– were put back on the agenda. Havel is eulogized by the usual suspects, but not by his numberless victims, who were pushed back into an abyss of exploitation by the Velvet revolution and other retrograde eruptions. With the fall of Communism allowing Havel and his brother to recover their family’s vast holdings, Havel’s life—he worked in a brewery under Communism—became much richer. The same can’t be said for countless others, whose better lives under Communism were swept away by a swindle that will, in the coming days, be lionized in the mass media on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the Soviet Union’s demolition. The anniversary is no time for celebration, except for the minority that has profited from it. For the bulk of us it ought to be an occasion to reflect on what the bottom 99 percent of humanity was able to achieve for ourselves outside the strictures, instabilities and unnecessary cruelties of capitalism.

Over the seven decades of its existence, and despite having to spend so much time preparing, fighting, and recovering from wars, Soviet socialism managed to create one of the great achievements of human history: a mass industrial society that eliminated most of the inequalities of wealth, income, education and opportunity that plagued what preceded it, what came after it, and what competed with it; a society in which health care and education through university were free (and university students received living stipends); where rent, utilities and public transportation were subsidized, along with books, periodicals and cultural events; where inflation was eliminated, pensions were generous, and child care was subsidized. By 1933, with the capitalist world deeply mired in a devastating economic crisis, unemployment was declared abolished, and remained so for the next five and a half decades, until socialism, itself was abolished. Excluding the war years, from 1928, when socialism was introduced, until Mikhail Gorbachev began to take it apart in the late 1980s, the Soviet system of central planning and public ownership produced unfailing economic growth, without the recessions and downturns that plagued the capitalist economies of North America, Japan and Western Europe. And in most of those years, the Soviet and Eastern European economies grew faster.

The Communists produced economic security as robust (and often more so) than that of the richest countries, but with fewer resources and a lower level of development and in spite of the unflagging efforts of the capitalist world to sabotage socialism. Soviet socialism was, and remains, a model for humanity — of what can be achieved outside the confines and contradictions of capitalism. But by the end of the 1980s, counterrevolution was sweeping Eastern Europe and Mikhail Gorbachev was dismantling the pillars of Soviet socialism. Naively, blindly, stupidly, some expected Gorbachev’s demolition project to lead the way to a prosperous consumer society, in which Soviet citizens, their bank accounts bulging with incomes earned from new jobs landed in a robust market economy, would file into colorful, luxurious shopping malls, to pick clean store shelves bursting with consumer goods. Others imagined a new era of a flowering multiparty democracy and expanded civil liberties, coexisting with public ownership of the commanding heights of the economy, a model that seemed to owe more to utopian blueprints than hard-headed reality.

Of course, none of the great promises of the counterrevolution were kept. While at the time the demise of socialism in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe was proclaimed as a great victory for humanity, not least by leftist intellectuals in the United States, two decades later there’s little to celebrate. The dismantling of socialism has, in a word, been a catastrophe, a great swindle that has not only delivered none of what it promised, but has wreaked irreparable harm, not only in the former socialist countries, but throughout the Western world, as well. Countless millions have been plunged deep into poverty, imperialism has been given a free hand, and wages and benefits in the West have bowed under the pressure of intensified competition for jobs and industry unleashed by a flood of jobless from the former socialist countries, where joblessness once, rightly, was considered an obscenity. Numberless voices in Russia, Romania, East Germany and elsewhere lament what has been stolen from them — and from humanity as a whole: “We lived better under communism. We had jobs. We had security.” And with the threat of jobs migrating to low-wage, high unemployment countries of Eastern Europe, workers in Western Europe have been forced to accept a longer working day, lower pay, and degraded benefits. Today, they fight a desperate rearguard action, where the victories are few, the defeats many. They too lived better — once.

But that’s only part of the story. For others, for investors and corporations, who’ve found new markets and opportunities for profitable investment, and can reap the benefits of the lower labor costs that attend intensified competition for jobs, the overthrow of socialism has, indeed, been something to celebrate. Equally, it has been welcomed by the landowning and industrial elite of the pre-socialist regimes whose estates and industrial concerns have been recovered and privatized. But they’re a minority. Why should the rest of us celebrate our own mugging?

Prior to the dismantling of socialism, most people in the world were protected from the vicissitudes of the global capitalist market by central planning and high tariff barriers. But once socialism fell in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, and with China having marched resolutely down the capitalist road, the pool of unprotected labor available to transnational corporations expanded many times over. Today, a world labor force many times larger than the domestic pool of US workers — and willing to work dirt cheap — awaits the world’s corporations. You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to figure out what the implications are for North American workers and their counterparts in Western Europe and Japan: an intense competition of all against all for jobs and industry. Inevitably, incomes fall, benefits are eroded, and working hours extended. Predictably, with labor costs tumbling, profits grow fat, capital surpluses accumulate and create bubbles, financial crises erupt and predatory wars to secure investment opportunities break out.

Growing competition for jobs and industry has forced workers in Western Europe to accept less. They work longer hours, and in some cases, for less pay and without increases in benefits, to keep jobs from moving to the Czech Republic, Slovakia and other former socialist countries — which, under the rule of the Reds, once provided jobs for all. More work for less money is a pleasing outcome for the corporate class, and turns out to be exactly the outcome fascists engineered for their countries’ capitalists in the 1930s. The methods, to be sure, were different, but the anti-Communism of Mussolini and Hitler, in other hands, has proved just as useful in securing the same retrograde ends. Nobody who is subject to the vagaries of the labor market – almost all of us — should be glad Communism was abolished.

Maybe some us don’t know we’ve been mugged. And maybe some of us haven’t been. Take the radical US historian Howard Zinn, for example, who, along with most other prominent Left intellectuals, greeted the overthrow of Communism with glee [1]. I, no less than others, admired Zinn’s books, articles and activism, though I came to expect his ardent anti-Communism as typical of left US intellectuals. To be sure, in a milieu hostile to Communism, it should come as no surprise that conspicuous displays of anti-Communism become a survival strategy for those seeking to establish a rapport, and safeguard their reputations, with a larger (and vehemently anti-Communist) audience.

But there may be another reason for the anti-Communism of those whose political views leave them open to charges of being soft on Communism, and therefore of having horns. As dissidents in their own society, there was always a natural tendency for them to identify with dissidents elsewhere – and the pro-capitalist, anti-socialist propaganda of the West quite naturally elevated dissidents in socialist countries to the status of heroes, especially those who were jailed, muzzled and otherwise repressed by the state. For these people, the abridgement of civil liberties anywhere looms large, for the abridgement of their own civil liberties would be an event of great personal significance. By comparison, the Reds’ achievements in providing a comfortable frugality and economic security to all, while recognized intellectually as an achievement of some note, is less apt to stir the imagination of one who has a comfortable income, the respect of his peers, and plenty of people to read his books and attend his lectures. He doesn’t have to scavenge discarded coal in garbage dumps to eke out a bare, bleak, and unrewarding existence. Some do.

Karol, 14, and his sister Alina, 12, everyday trudge to a dump, where mixed industrial waste is deposited, just outside Swietochlowice, in formerly socialist Poland. There, along with their father, they look for scrap metal and second grade coal, anything to fetch a few dollars to buy a meager supply of groceries. “There was better life in Communism,” says Karol’s father, 49, repeating a refrain heard over and over again, not only in Poland, but also throughout the former socialist countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. “I was working 25 years for the same company and now I cannot find a job – any job. They only want young and skilled workers.” [2] According to Gustav Molnar, a political analyst with the Laszlo Teleki Institute, “the reality is that when foreign firms come here, they’re only interested in hiring people under 30. It means half the population is out of the game.” [3] That may suit the bottom lines of foreign corporations – and the overthrow of socialism may have been a pleasing intellectual outcome for well-fed, comfortable intellectuals from Boston – but it hardly suits that part of the Polish population that must scramble over mountains of industrial waste – or perish. Maciej Gdula, 34, a founding member of the group, Krytyka Polityczna, or Political Critique, complains that many Poles “are disillusioned with the unfulfilled promises of capitalism. They promised us a world of consumption, stability and freedom. Instead, we got an entire generation of Poles who emigrated to go wash dishes.” [4] Under socialism “there was always work for everybody” [5] – at home. And always a place to live, free schools to go to, and doctors to see, without charge. So why was Howard Zinn glad that Communism was overthrown?

That the overthrow of socialism has failed to deliver anything of benefit to the majority is plain to see. One decade after counterrevolution skittered across Eastern Europe, 17 former socialist countries were immeasurably poorer. In Russia, poverty had tripled. One child in 10 – three million Russian children – lived like animals, ill-fed, dressed in rags, and living, if they were lucky, in dirty, squalid flats. In Moscow alone, 30,000 to 50,000 children slept in the streets. Life expectancy, education, adult-literacy and income declined. A report by the European Children’s Trust, written in 2000, revealed that 40 percent of the population of the former socialist countries – a number equal to one of every two US citizens – lived in poverty. Infant mortality and tuberculosis were on the rise, approaching Third World levels. The situation, according to the UN, was catastrophic. And everywhere the story was the same. [6, 7, 8, 9]

Paul Cockshot points out that:

The restoration of the market mechanism in Russia was a vast controlled experiment. Nation, national character and culture, natural resources and productive potential remained the same, only the economic mechanism changed. If Western economists were right, then we should have expected economic growth and living standards to have leapt forward after the Yeltsin shock therapy. Instead the country became an economic basket-case. Industrial production collapsed, technically advanced industries atrophied, and living standards fell so much that the death rate shot up by over a third leading to some 7.7 million extra deaths.

For many Russians, life became immeasurably worse.

If you were old, if you were a farmer, if you were a manual worker, the market was a great deal worse than even the relatively stagnant Soviet economy of Brezhnev. The recovery under Putin, such as it was, came almost entirely as a side effect of rising world oil prices, the very process that had operated under Brezhnev. [10]

While the return of capitalism made life harsher for some, it proved lethal for others. From 1991 to 1994, life expectancy in Russia tumbled by five years. By 2008, it had slipped to less than 60 years for Russian men, a full seven years lower than in 1985 when Gorbachev came to power and began to dismantle Soviet socialism. Today “only a little over half of the ex-Communist countries have regained their pretransition life-expectancy levels,” according to a study published in the medical journal, The Lancet. [11]

“Life was better under the Communists,” concludes Aleksandr. “The stores are full of things, but they’re very expensive.” Victor pines for the “stability of an earlier era of affordable health care, free higher education and housing, and the promise of a comfortable retirement – things now beyond his reach.” [12] A 2008 report in the Globe and Mail, a Canadian newspaper, noted that “many Russians interviewed said they still grieve for their long, lost country.” Among the grievers is Zhanna Sribnaya, 37, a Moscow writer. Sribnaya remembers “Pioneer camps when everyone could go to the Black Sea for summer vacations. Now, only people with money can take those vacations.” [13]

Ion Vancea, a Romanian who struggles to get by on a picayune $40 per month pension says, “It’s true there was not much to buy back then, but now prices are so high we can’t afford to buy food as well as pay for electricity.” Echoing the words of many Romanians, Vancea adds, “Life was 10 times better under (Romanian Communist Party leader Nicolae) Ceausescu.” [14] An opinion poll carried out last year found that Vancea isn’t in the minority. Conducted by the Romanian polling organisation CSOP, the survey found that almost one-half of Romanians thought life was better under Ceauşescu, compared to less than one-quarter who thought life is better today. And while Ceauşescu is remembered in the West as a Red devil, only seven percent said they suffered under Communism. Why do half of Romanians think life was better under the Reds? They point to full employment, decent living conditions for all, and guaranteed housing – advantages that disappeared with the fall of Communism. [15]

Next door, in Bulgaria, 80 percent say they are worse off now that the country has transitioned to a market economy. Only five percent say their standard of living has improved. [16] Mimi Vitkova, briefly Bulgaria’s health minister for two years in the mid-90s, sums up life after the overthrow of socialism: “We were never a rich country, but when we had socialism our children were healthy and well-fed. They all got immunized. Retired people and the disabled were provided for and got free medicine. Our hospitals were free.” But things have changed, she says. “Today, if a person has no money, they have no right to be cured. And most people have no money. Our economy was ruined.” [17] A 2009 poll conducted by the Pew Global Attitudes Project found that a paltry one in nine Bulgarians believe ordinary people are better off as a result of the transition to capitalism. And few regard the state as representing their interests. Only 16 percent say it is run for the benefit of all people. [18]

In the former East Germany a new phenomenon has arisen: Ostalgie, a nostalgia for the GDR. During the Cold War era, East Germany’s relative poverty was attributed to public ownership and central planning – sawdust in the gears of the economic engine, according to anti-socialist mythology. But the propaganda conveniently ignored the fact that the eastern part of Germany had always been less developed than the west, that it had been plundered of its key human assets at the end of World War II by US occupation forces, that the Soviet Union had carted off everything of value to indemnify itself for its war losses, and that East Germany bore the brunt of Germany’s war reparations to Moscow. [19] On top of that, those who fled East Germany were said to be escaping the repression of a brutal regime, and while some may indeed have been ardent anti-Communists fleeing repression by the state, most were economic refugees, seeking the embrace of a more prosperous West, whose riches depended in large measure on a history of slavery, colonialism, and ongoing imperialism—processes of capital accumulation the Communist countries eschewed and spent precious resources fighting against.

Today, nobody of an unprejudiced mind would say that the riches promised East Germans have been realized. Unemployment, once unheard of, runs in the double digits and rents have skyrocketed. The region’s industrial infrastructure – weaker than West Germany’s during the Cold War, but expanding — has now all but disappeared. And the population is dwindling, as economic refugees, following in the footsteps of Cold War refugees before them, make their way westward in search of jobs and opportunity. [20] “We were taught that capitalism was cruel,” recalls Ralf Caemmerer, who works for Otis Elevator. “You know, it didn’t turn out to be nonsense.” [21] As to the claim that East Germans have “freedom” Heinz Kessler, a former East German defense minister replies tartly, “Millions of people in Eastern Europe are now free from employment, free from safe streets, free from health care, free from social security.” [22] Still, Howard Zinn was glad communism collapsed. But then, he didn’t live in East Germany.

So, who’s doing better? Vaclav Havel, the Czech playwright turned president, came from a prominent, vehemently anti-socialist Prague family, which had extensive holdings, “including construction companies, real estate and the Praque Barrandov film studios”. [23] The jewel in the crown of the Havel family holdings was the Lucerna Palace, “a pleasure palace…of arcades, theatres, cinemas, night-clubs, restaurants, and ballrooms,” according to Frommer’s. It became “a popular spot for the city’s nouveau riches to congregate,” including a young Havel, who, raised in the lap of luxury by a governess, doted on by servants, and chauffeured around town in expensive automobiles, “spent his earliest years on the Lucerna’s polished marble floors.” Then, tragedy struck – at least, from Havel’s point of view. The Reds expropriated Lucerna and the family’s other holdings, and put them to use for the common good, rather than for the purpose of providing the young Havel with more servants. Havel was sent to work in a brewery.

“I was different from my schoolmates whose families did not have domestics, nurses or chauffeurs,” Havel once wrote. “But I experienced these differences as disadvantage. I felt excluded from the company of my peers.” [24] Yet the company of his peers must not have been to Havel’s tastes, for as president, he was quick to reclaim the silver spoon the Reds had taken from his mouth. Celebrated throughout the West as a hero of intellectual freedom, he was instead a hero of capitalist restoration, presiding over a mass return of nationalized property, including Lucerna and his family’s other holdings.

The Roman Catholic Church is another winner. The pro-capitalist Hungarian government has returned to the Roman Catholic Church much of the property nationalized by the Reds, who placed the property under common ownership for the public good. With recovery of many of the Eastern and Central European properties it once owned, the Church is able to reclaim its pre-socialist role of parasite — raking in vast amounts of unearned wealth in rent, a privilege bestowed for no other reason than it owns title to the land. Hungary also pays the Vatican a US$9.2 million annuity for property it has been unable to return. [25] (Note that a 2008 survey of 1,000 Hungarians by the Hungarian polling firm Gif Piackutato found that 60 percent described the era of Communist rule under Red leader Janos Kadar as Hungary’s happiest while only 14 percent said the same about the post-Communist era. [26])

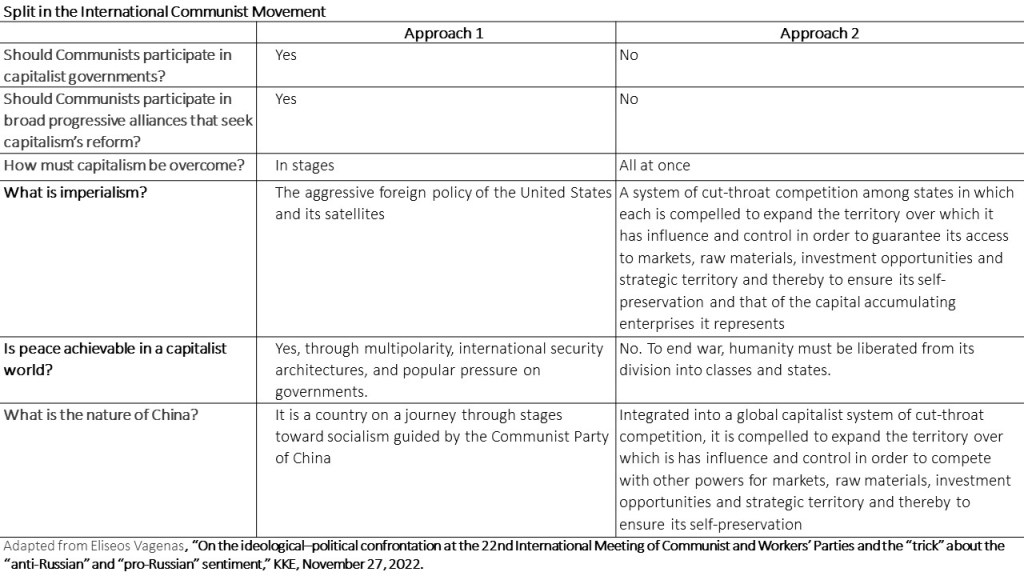

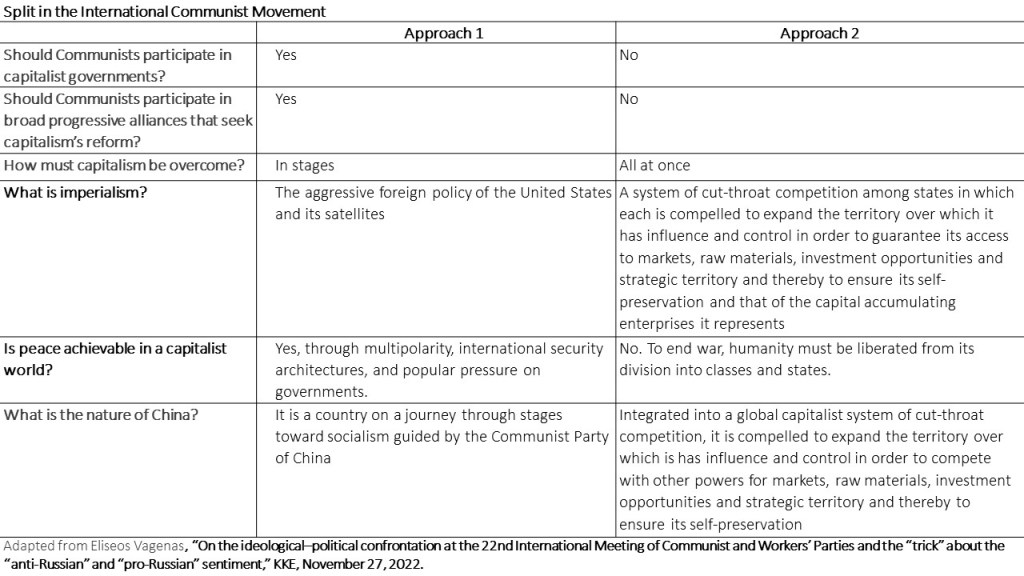

The Church, former landowners, and CEOs aside, most people of the former socialist bloc aren’t pleased that the gains of the socialist revolutions have been reversed. Three-quarters of Russians, according to a 1999 poll [27] regret the demise of the Soviet Union. And their assessment of the status quo is refreshingly clear-sighted. Almost 80 percent recognize liberal democracy as a front for a government controlled by the rich. A majority (correctly) identifies the cause of its impoverishment as an unjust economic system (capitalism), which, according to 80 percent, produces “excessive and illegitimate inequalities.” [28] The solution, in the view of the majority, is to return to socialism, even if it means one-party rule. Russians, laments the anti-Communist historian Richard Pipes, haven’t Americans’ taste for multiparty democracy, and seem incapable of being cured of their fondness for Soviet leaders. In one poll, Russians were asked to list the 10 greatest people of all time, of all nations. Lenin came in second, Stalin fourth and Peter the Great came first. Pipes seems genuinely distressed they didn’t pick his old boss, Ronald Reagan, and is fed up that after years of anti-socialist, pro-capitalist propaganda, Russians remain committed to the idea that private economic activity should be restricted, and “the government [needs] to be more involved in the country’s economic life.” [29] An opinion poll which asked Russians which socio-economic system they favor, produced these results.

• State planning and distribution, 58%;

• Based on private property and distribution, 28%;

• Hard to say, 14%. [30]

So, if the impoverished peoples of the formerly socialist countries pine for the former attractions of socialism, why don’t they vote the Reds back in? Socialism can’t be turned on with the flick of a switch. The former socialist economies have been privatized and placed under the control of the market. Those who accept the goals and values of capitalism have been recruited to occupy pivotal offices of the state. And economic, legal and political structures have been altered to accommodate private production for profit. True, there are openings for Communist parties to operate within the new multiparty liberal democracies, but Communists now compete with far more generously funded parties in societies in which their enemies have restored their wealth and privileges and use them to tilt the playing field strongly in their favor. They own the media, and therefore are in a position to shape public opinion and give parties of private property critical backing during elections. They spend a king’s ransom on lobbying the state and politicians and running think-tanks which churn out policy recommendations and furnish the media with capitalist-friendly “expert” commentary. They set the agenda in universities through endowments, grants and the funding of special chairs to study questions of interest to their profits. They bring politicians under their sway by doling out generous campaign contributions and promises of lucrative post-political career employment opportunities. Is it any wonder the Reds aren’t simply voted back into power? Capitalist democracy means democracy for the few—the capitalists—not a level-playing field where wealth, private-property and privilege don’t matter.

And anyone who thinks Reds can be elected to office should reacquaint themselves with US foreign policy vis-a-vis Chile circa 1973. The United States engineered a coup to overthrow the socialist Salvador Allende, on the grounds that Chileans couldn’t be allowed to make the ”irresponsible” choice of electing a man Cold Warriors regarded as a Communist. More recently, the United States, European Union and Israel, refused to accept the election of Hamas in the Palestinian territories, all the while hypocritically presenting themselves as champions and guardians of democracy.

Of course, no forward step will be taken, can be taken, until a decisive part of the population becomes disgusted with and rejects what exists today, and is convinced something better is possible and is willing to tolerate the upheavals of transition. Something better than unceasing economic insecurity, private (and for many, unaffordable) health care and education, and vast inequality, is achievable. The Reds proved that. It was the reality in the Soviet Union, in China (for a time), in Eastern Europe, and today, hangs on in Cuba and North Korea, despite the incessant and far-ranging efforts of the United States to crush it.

It should be no surprise that Vaclav Havel, as others whose economic and political supremacy was, for a time, ended by the Reds, was a tireless fighter against socialism, and that he, and others, who sought to reverse the gains of the revolution, were cracked down on, and sometimes muzzled and jailed by the new regimes. To expect otherwise is to turn a blind eye to the determined struggle that is carried on by the enemies of socialism, even after socialist forces have seized power. The forces of reaction retain their money, their movable property, the advantages of education, and above all, their international connections. To grant them complete freedom is to grant them a free hand to organize the downfall of socialism, to receive material assistance from abroad to reverse the revolution, and to elevate the market and private ownership once again to the regulating principles of the economy. Few champions of civil liberties argue that in the interests of freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and freedom of the press, that Germans ought to be allowed to hold pro-Nazi rallies, establish a pro-Nazi press, and organize fascist political parties, to return to the days of the Third Reich. To survive, any socialist government, must, of necessity, be repressive toward its enemies, who, like Havel, will seek their overthrow and the return of their privileged positions. This is demonized as totalitarianism by those who have an interest in seeing anti-socialist forces prevail, regard civil and political liberties (as against a world of plenty for all) as the pinnacle of human achievement, or have an unrealistically sanguine view of the possibilities for the survival of socialist islands in a sea of predatory capitalist states.

Where Reds have prevailed, the outcome has been far-reaching material gain for the bulk of the population: full employment, free health care, free education through university, free and subsidized child care, cheap living accommodations and inexpensive public transportation. Life expectancy has soared, illiteracy has been wiped out, and homelessness, unemployment and economic insecurity have been abolished. Racial strife and ethnic tensions have been reduced to almost the vanishing point. And inequalities in wealth, income, opportunity, and education have been greatly reduced. Where Reds have been overthrown, mass unemployment, underdevelopment, hunger, disease, illiteracy, homelessness, and racial conflict have recrudesced, as the estates, holdings and privileges of former fat cats have been restored. Communists produced gains in the interest of all humanity, achieved in the face of very trying conditions, including the unceasing hostility of the West and the unremitting efforts of the former exploiters to restore the status quo ante.

1. Howard Zinn, “Beyond the Soviet Union,” Znet Commentary, September 2, 1999.

2. “Left behind by the luxury train,” The Globe and Mail, March 29, 2000.

3. “Support dwindling in Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland,” The Chicago Tribune, May 27, 2001.

4. Dan Bilefsky, “Polish left gets transfusion of young blood,” The New York Times, March 12, 2010.

5. “Support dwindling in Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland,” The Chicago Tribune, May 27, 2001.

6. “An epidemic of street kids overwhelms Russian cities,” The Globe and Mail, April 16, 2002.

7. “UN report says one billion suffer extreme poverty,” World Socialist Web Site, July 28, 2003.

8. Associated Press, October 11, 2000.

9. “UN report….

10. Paul Cockshott, “Book review: Red Plenty by Francis Spufford”, Marxism-Leninism Today, http://mltoday.com/en/subject-areas/books-arts-and-literature/book-review-red-plenty-986-2.html

11. David Stuckler, Lawrence King and Martin McKee, “Mass Privatization and the Post-Communist Mortality Crisis: A Cross-National Analysis,” Judy Dempsey, “Study looks at mortality in post-Soviet era,” The New York Times, January 16, 2009.

12. “In Post-U.S.S.R. Russia, Any Job Is a Good Job,” New York Times, January 11, 2004.

13. Globe and Mail (Canada), June 9, 2008.

14. “Disdain for Ceausescu passing as economy worsens,” The Globe and Mail, December 23, 1999.

15. James Cross, “Romanians say communism was better than capitalism”, 21st Century Socialism, October 18, 2010. http://21stcenturysocialism.com/article/romanians_say_communism_was_better_than_capitalism_02030.html “Opinion poll: 61% of Romanians consider communism a good idea”, ActMedia Romanian News Agency, September 27, 2010. http://www.actmedia.eu/top+story/opinion+poll%3A+61%25+of+romanians+consider+communism+a+good+idea/29726

16. “Bulgarians feel swindled after 13 years of capitalism,” AFP, December 19, 2002.

17. “Bulgaria tribunal examines NATO war crimes,” Workers World, November 9, 2000.

18. Matthew Brunwasser, “Bulgaria still stuck in trauma of transition,” The New York Times, November 11, 2009.

19. Jacques R. Pauwels, “The Myth of the Good War: America in the Second World War,” James Lorimer & Company, Toronto, 2002. p. 232-235.

20. “Warm, Fuzzy Feeling for East Germany’s Grey Old Days,” New York Times, January 13, 2004.

21. “Hard lessons in capitalism for Europe’s unions,” The Los Angeles Times, July 21, 2003.

22. New York Times, July 20, 1996, cited in Michael Parenti, “Blackshirts & Reds: Rational Fascism & the Overthrow of Communism,” City Light Books, San Francisco, 1997, p. 118.

23. Leos Rousek, “Czech playwright, dissident rose to become president”, The Wall Street Journal, December 19, 2011.

24. Dan Bilefsky and Jane Perlez, “Czechs’ dissident conscience, turned president”, The New York Times, December 18, 2011.

25. U.S. Department of State, “Summary of Property Restitution in Central and Eastern Europe,” September 10, 2003. http://www.state.gov/p/eur/rls/or/2003/31415.htm

26. “Poll shows majority of Hungarians feel life was better under communism,” May 21, 2008, www.politics.hu

27. Cited in Richard Pipes, “Flight from Freedom: What Russians Think and Want,” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2004.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. “Russia Nw”, in The Washington Post, March 25, 2009.