By Stephen Gowans

If legitimacy and moral principle mattered, a groundswell of effective popular resistance would have arisen in NATO countries and brought the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to an end long ago. But vigorous opposition is inspired by more than ideals; it happens when war has very real personal consequences for a large part of the population. In the NATO countries, this has not been true of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which have been fought with light causalities to a tiny fraction of the population that makes up a volunteer, professional military; have led to no major tax increases; and have provoked few disruptions due to retaliatory terrorist attacks. By contrast, the wars have had very real, tragic, personal consequences for large parts of the Afghan and Iraqi populations. Asymmetrical conditions (intolerable ones for the people of Afghanistan and Iraq; life lived much as it always is in the aggressor countries) produce asymmetrical responses (a determined armed resistance in Afghanistan and Iraq; a weak anti-war movement in the aggressor countries.)

Absence of Legitimacy

While it’s true that large numbers of people have been opposed to the war on Iraq from its formal beginning in 2003, those who said there was no credible evidence that Saddam Hussein’s Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, that the WMD angle was a transparent pretext, that the war was for oil, and that it (along with the war on Afghanistan) wouldn’t lessen threats to the US and Britain but increase them, were in the minority. They were dismissed in various ways: as loony and pro-authoritarian, as having never met a dictator they didn’t like, as thug-huggers and apologists for terrorism, and so on.

Others, perhaps intimidated by the ridicule they saw heaped upon this minority and afraid of departing too far from the mainstream of mass media-approved opinion, compromised. Some called for more sanctions rather than war, although sanctions, which are simply war by other means, had already led to the deaths of half a million Iraqi children under the age of five(1)and perhaps as many people over five. Perhaps their concern was chauvinistic: not that Iraqis were being killed, but that US and British troops might get killed. Or maybe they didn’t know that sanctions are indeed directed at ordinary people. After all, the politicians who imposed them kept assuring everyone that sanctions only hurt the leadership of target countries, not the people.

The cowardly, afraid they would be tarred as dictator-lovers, issued statements denouncing both sides – the aggressor and the intended victim, as if, on the eve of the Nazi invasion of Poland, they had declared, “We like neither the Nazis nor the Poles,” in case, in opposing the Nazi action, they should be accused of supporting Polish politics.

Some of these people thought they were being clever. If they said (quite truthfully though irrelevantly) that they hated Saddam Hussein because he was a dictator, they could take the dictator-lover charge off the table, and focus public attention on US actions. But all they did was help to give heart to those seeking a silver lining in the dark cloud of impending war. “The war might be conducted for the wrong reasons,” rationalized the silver lining seekers, “but at least some good will come of it. The world will be rid of a vicious dictator.”

Perhaps the largest part of the sector that opposed the war did so, not because the war was nakedly imperialist and would increase the threat to Americans by further inflaming anger against US domination of the Middle East, but because they were Democrats and this was Bush’s war. Likewise, there were many Republicans who opposed the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia, not because it was nakedly imperialist, but because it was Clinton’s war. The Democrats who opposed the Iraq war weren’t anti-war or anti-imperialist, they were anti-Bush. And the Republicans who opposed the Kosovo air war weren’t anti-war or anti-imperialist, they were anti-Clinton. Part of the reason the anti-war movement, which has been mostly a part-time affair limited to a series of ritualized, orderly, marches, has virtually died out, is because Bush – the impetus for opposition to the wars – has retired to his ranch in Texas. Protest, at least in the view of partisan Democrats, is no longer necessary; indeed, from their point of view, it is to be vigorously avoided.

Withdrawal: An Exercise in Semantics

Today, the war in Iraq is in the midst of a US troop draw down, but not as the beginning to the end of US military involvement in Iraq. The real purpose is to redeploy troops to Afghanistan, where, with the war going poorly for the Pentagon, more troops are needed. US military occupation of Iraq is open-ended.

The withdrawal, which will reduce the number of American troops to 50,000 — from 112,000 earlier this year and close to 165,000 at the height of the surge — is … an exercise in semantics. What soldiers today would call combat operations — hunting insurgents, joint raids between Iraqi security forces and United States Special Forces to kill or arrest militants — will be called “stability operations.” Beyond August the next Iraq deadline is the end of 2011, when all American troops are supposed to be gone. But few believe that America’s military involvement in Iraq will end then. The conventional wisdom among military officers, diplomats and Iraqi officials is that after a new government is formed, talks will begin about a longer-term American troop presence. (2)

A longer-term American troop presence is exactly what US Secretary of War Robert Gates in 2007 told Congress could be expected. He said he envisioned keeping at least five combat brigades in Iraq as a long term presence, which is equal to about 20,000 combat personnel with an equal number of support staff. (3) The US military spokesman in Iraq, Major General Stephen Lanza, assured supporters of a US troop presence in Iraq that despite the troop draw-down, “In practical terms, nothing will change.” (4)

Meanwhile, the US government isn’t just rebranding the occupation, it’s also privatising it. There are around 100,000 private contractors working for the occupying forces, of whom more than 11,000 are armed mercenaries, mostly “third country nationals”, typically from the developing world. … The US now wants to expand their numbers sharply in what Jeremy Scahill, who helped expose the role of the notorious US security firm Blackwater, calls the “coming surge” of contractors in Iraq. Hillary Clinton wants to increase the number of military contractors working for the state department alone from 2,700 to 7,000, to be based in five “enduring presence posts” across Iraq. (5)

Colonialism without Colonies

The 1980 Carter Doctrine identified Persian Gulf oil as a US national security interest. In plain language, this meant that the petroleum rich countries of the Persian Gulf would be reserved as an area open to exploitation by US business enterprises and investors. The US would tolerate no attempt by other outside forces – or internal forces either — to control the region’s petro-reserves, and thereby deny or limit US enterprises access to the region’s oil and gas on preferential terms. Access would be guaranteed to ensure that US oil majors reaped a bonanza of profits from the sale of Middle Eastern oil to its principal consumers, namely Western Europe and Japan, and not primarily to guarantee sufficient oil to run the US military machine and economy, as is commonly supposed. Indeed, while the United States relies on oil from the Middle East, it has access to plentiful supplies of fossil fuels from sources that are much closer to hand: Canada (which has the world’s largest reserves of oil after Saudi Arabia); Venezuela (sixth in the world in oil reserves); and from its own oil wells. (6)

The Carter Doctrine was the modern version of colonialism. Under the old one, an outside power claims a territory as its own for the purposes of monopolizing its land, labor, markets and raw materials for the enrichment of its dominant politico-economic interests, its ruling class. It does so by planting its flag, appointing a governor, and establishing a military garrison. This announces to the world that use of this territory is exclusively at the discretion of the colonial power, and that the monopoly is backed by the colonial power’s military.

Under the Carter Doctrine, Washington would leave the flags, constitutions, currencies and leaders of the nominally independent Middle Eastern countries in place. But it would be understood that these countries would open themselves to exploitation by US business enterprises, if they weren’t already, or would remain open, if they were. The Pentagon would be the ultimate enforcer, ensuring that investment opportunities remained available on preferential terms to US businesspeople and that US investments were kept free from the threat of expropriation, or limitation by high taxes, stringent regulations, strong unions, restraints on repatriation of profits, and affirmative action programs designed to promote local businesses. Whereas the colonial powers had carved out territories for themselves and ipso facto claimed them as their own, Carter simply said what amounted to, “This now belongs to the United States on a de facto basis and anyone who says otherwise will have to deal with the Pentagon.” Significantly, this warning wasn’t directed at outside powers alone; it was also intended for communist, socialist and nationalist forces, who might take it into their heads that the land on which they lived and their raw materials ought to be collectively or publicly owned for the benefit of the local population or turned over to the local bourgeoisie to spur independent internal development.

Iran (after 1979) and Iraq were a problem. Nationalists were in power in both countries. Washington provided military assistance to help Iraq in its war against Iran, hoping the two nationalist powers would exhaust and weaken each other in war, and, in the aftermath, Washington could step in to assert control. When Iraq invaded Kuwait with what it believed was tacit US approval (7), Washington used the event to initiate a war against Iraq that continues today. The eventual invasion of Iraq was carried out under the Wolfowitz Doctrine, which said the United States would prevent the emergence of a regional Middle Eastern power capable of monopolizing the region’s petroleum resources, but which really meant that regional oil powers, like Iraq and Iran, would be prevented from controlling their own petroleum resources. George W. Bush pointed to preventing “a world in which these extremists and radicals got control of energy resources” (8) as the rationale for US military strategy in the Persian Gulf. What made the objects of Bush’s alarm “extreme” and “radical” was that they weren’t prepared to surrender control of their oil and gas to US corporations.

The Insecurity State

Fighting terrorism and preventing Iran from developing nuclear weapons has become the rationale for US military domination of the Middle East. Yet it was US military domination of the Middle East that sparked terrorist attacks against US targets in the first place, and established the conditions that pressure Iran to develop nuclear weapons (which isn’t to say that Iran is developing nuclear weapons, only that the need to build a defense against US and Israeli aggression makes it more likely that it will.)

What motivates Osama bin Laden and his followers has largely been kept from Western audiences, who have been fed pabulum about al Qaeda’s “hatred of our freedoms,” but it is clear that bin Laden’s campaign of terrorism is a reaction to US imperialism in the Middle East. He importunes his followers to strike the United States because:

…the United States has been occupying the lands of Islam in the holiest of places, the Arabian Peninsula, plundering its riches, dictating to its rulers, humiliating its people, terrorising its neighbours, and turning its bases in the Peninsula into a spearhead through which to fight the neighboring Muslim peoples. (9)

On another occasion bin Laden explained that:

The ruling to kill the Americans and their allies—civilians and military—is an individual duty for every Muslim who can do it in any country in which it is possible to do it, in order to liberate the al-Aqsa Mosque and the holy Mosque from their grip, and in order for their armies to move out of all the lands of Islam, defeated and unable to threaten any Muslim. (10)

Having operated on behalf of the CIA to oppose Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan in the 1980s, bin Laden is sometimes said to be a creation of the United States, a kind of Frankenstein monster. But receiving assistance from a state does not make one its creation. Bin Laden would have militantly opposed Soviet intervention in Afghanistan whether the CIA helped him out or not. There is, however, a sense in which bin Laden is, indeed, a creation of the United States, or more precisely, a reaction against its policies. Bin Laden, as a fighter against US domination of the Middle East, wouldn’t exist were it not for the United States stationing troops in Saudi Arabia, and now Iraq and Afghanistan; were the United States not the guarantor of Israel’s existence as an anti-Arab settler state; and had Washington not created a string of marionette rulers throughout the Arab world. In seeking to extend and consolidate US hegemony on behalf of the United States’ dominant economic class, these policies have had the effect of stirring up a nest of hornets. Once stirred up, the danger the hornets pose become a pretext for further extension of US hegemony to deny the hornets sanctuary and a base of operations from which they can inflict harm. As Victor Kiernan once remarked: “Now, as on other occasions, it appear[s] that American security require(s) everyone else to be insecure.” (11)

Right All Along

The ridiculed minority was right. The Iraq war was – and continues to be – about oil; there never were any weapons of mass destruction; Iraq posed no danger to the West; and rather than lessening the threat of terrorist attack, it has increased it. As for the idea, promulgated by Barack Obama as justification for his war policy in Afghanistan, that Afghanistan must be occupied by US forces and the militaries of its allies in order to prevent the country from becoming a base of operations for al-Qaeda, it can be pointed out that terrorist attacks can be – and have been – plotted and organized just about anywhere. William Blum asks:

[W]hat actually is needed to plot to buy airline tickets and take flying lessons in the United States? A room with some chairs? What does “an even larger safe haven” mean? A larger room with more chairs? Perhaps a blackboard? Terrorists intent upon attacking the United States can meet almost anywhere, with Afghanistan probably being one of the worst places for them, given the American occupation. (12)

Indeed, it is very unlikely that al-Qaeda is the position to establish a base of operations in Afghanistan, a point made by Stephen Biddle, a scholar at the uber-establishment Council on Foreign Relations, who advised General Stanley McChrystal, the former US commander in Afghanistan. Biddle “said the chance of a new Qaeda stronghold that could threaten American territory was relatively low” equating the odds of this happening “to a 50-year-old dying in the next year in America” which he said was “substantially less than 1 percent.” So why carry on an occupation whose costs approach $1 trillion (13) in order to avert an event that has virtually no chance of happening? Because, says Biddle – who advances an argument that is perhaps one of the least cogent ever — “It’s like buying life insurance” and “most Americans buy life insurance.” (14)

Richard Boucher had a different view. When he spoke on September 20, 2007 at the Paul H. Nitze School for Advanced International Studies in Washington, he was US Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs. Boucher’s account of why the United States has spent countless dollars on war in Afghanistan had nothing to do with insurance policies and much to do with oil and gas. “One of our goals is to stabilize Afghanistan, so it can become a conduit and a hub between South and Central Asia so that energy can flow to the south,” he explained. (15) Boucher’s views mesh with Biddle’s if we take “stabilize” to mean pacifying forces opposed to the United States controlling Afghanistan as a hub between South and Central Asia.

Fadhil Chalabi, an adviser to Washington in the lead-up to the invasion of Iraq and later Iraq’s oil undersecretary of state, described the invasion of Iraq as “a strategic move on the part of the United States of America and the UK to have a military presence in the Gulf in order to secure [oil] supplies in the future”. (16) He echoed the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve Bank, Alan Greenspan, who, in his memoirs, The Age of Turbulence, lamented “that it is politically inconvenient to acknowledge what everyone knows: the Iraq war is largely about oil.” (17) George W. Bush himself, in worrying that “extremists would control a key part of the world’s energy supply” if the US did not have a troop presence in Iraq, indirectly acknowledged that oil was central to the reason he ordered an invasion of the country. (18) But it should be recalled that it is not the need to guarantee a secure supply of Middle Eastern oil for US consumers that was central to the reason for the invasion, for the US has access to plentiful oil from sources close to home. What really counted was the attraction of securing a bonanza of profits for US oil majors from the sale of Middle Eastern oil to Western Europe and Japan. A subsidiary benefit also figured in the equation: if Washington controls Japan’s and Western Europe’s oil supply, it controls Japan and Western Europe. (19)

Testifying before the Chilcot Inquiry into the Britain’s role in the Iraq war, Baroness Manningham-Buller, the former director general of Britain’s domestic intelligence agency, MI-5, confirmed what the minority had said eight years earlier: “That Iraq had presented little threat … before the invasion”(20) and that fears that “Saddam could have linked terrorists to weapons of mass destruction, facilitating their use against the west…certainly wasn’t of concern in either the short term or the medium term.” (21)

Manningham-Buller also testified that “the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan had greatly increased the terrorist threat” and that “involvement in Iraq, for want of a better word, radicalized a whole generation of young people — not a whole generation, a few among a generation — who saw our involvement in Iraq, on top of our involvement in Afghanistan, as being an attack on Islam.”(22)

Democracy for the Few

The majority of citizens of the aggressor countries are opposed to their governments deploying their nations’ troops to Iraq and Afghanistan,(23)and yet the wars go on. US voters elected a president whose equivocations led them to believe he would end the wars, although the letter of what he said was never anti-war. The wars continue, just as they did under his predecessor. The Nobel committee (grotesquely) gave the new US president the Peace Prize, hoping it might nudge him to declare peace. Its members’ hopes were dashed. There never were weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and yet the occupation of Iraq continues, and will for the foreseeable future, by both US troops engaged in combat operations under a new name that draws a veil over their continued combat role and private sector mercenaries hired by the United States. The reasons for conducting the wars have been shown to be false, and yet talk of bringing US military intervention to a close is merely a sop to public opinion. The conventional wisdom among decision-makers is that a significant US troop presence will continue in both countries beyond 2011.(24) Even if US troops are repatriated (or redeployed to the next war for profits), the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will continue anyway through local surrogates: the US-trained, equipped and directed Iraq and Afghanistan (and Pakistan) armies, to say nothing of US State Department-hired mercenaries.

In a true democracy, the decisions made within the society reflect the interests of the majority. Does anyone believe the wars on Iraq and Afghanistan are waged in the interests of the majority?

We?

It is commonplace to refer to the waging of the wars as if it is something that legitimately involves the plural “we”, as in: “we” are still in Afghanistan, and when are “we” going to get out of Iraq? There is no “we”. “We” weren’t asked to consent to the wars, “we” don’t support them, and “we” don’t benefit from them. The reality is that “we” don’t matter, except insofar as we have to be tossed a lagniappe every now and then to prevent our opposition from escalating to levels that would threaten to destabilize the rule of those who, from the system’s perspective, really do matter.

On the other hand, “we” are not really burdened by the wars, either. “We” don’t fight them, or not many of us do. A small minority of volunteer professional soldiers and private sector mercenaries fight the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and they fight in ways that minimize the number of their casualties. And because “we” don’t fight the wars, even though “we” oppose them and “we” don’t benefit from them, it doesn’t really matter whether “we” are opposed morally and intellectually. Foreign policy is shaped without reference to public opinion and in complete isolation from it, and therefore the moral and intellectual opposition of majorities counts for little. Foreign policy, it should be clear, doesn’t depend on public opinion as an input. That’s not to say it can’t be shaped by pressure from below, but the pressure that alters foreign policy doesn’t come in the form of ritualized, non-disruptive expressions of popular opposition: the orderly and nonviolent march; petitions and letter writing campaigns; letters sent to editors of newspapers, and so on. The fact that all of these things have been done and continue to be done without the slightest discernible effect is proof enough. No, foreign policy bends from pressure that disrupts the normal functioning of society and therefore threatens the interests of the dominant economic class; in other words, from activities that are “incompatible with the stability required by big business for the tranquil digestion of profits.” (25) And foreign policy becomes something other than an expression of the class interests of big business, that at best can be momentarily restrained only by enormous pressure from below, when the authority to make foreign policy is wrested from the control of big business’s representatives and reconstituted on the basis of a different class altogether.

But bringing about reforms within the system (that is actually bringing them about and not simply registering dissent), much less changing the system altogether, requires a willingness to accept all manner of risks, dangers and penalties: trouble with the police and security services and the potential of going to jail or being forced to live underground. While a small minority may be prepared to accept these risks as the price of pursuing their moral and intellectual ideals, most people are not made in the mold of Che Guevara. Mass movements for change that disrupt the tranquil digestion of profits arise when conditions become intolerable for the mass of people – so intolerable that the considerable costs of acting to change them are outweighed by the costs exacted by the conditions themselves. It is no surprise that the anti-Vietnam War movement in the United States was student-led. It was students who faced the unwelcome prospect of being sent to Southeast Asia to kill or be killed. It wasn’t until the war led to tax increases that opposition in the wider society was aroused. But as “soon as the risk of having to serve at the front was removed, agitation and concern over Vietnamese sufferings died down abruptly; a year or two more, and Vietnam was forgotten.”(26)In the end, it wasn’t the student movement that brought the war to a close; it was the resistance of the people for whom the conditions of the war and decades of colonial domination had proved intolerable: the Vietnamese.

Cost of War

It’s worth quoting an Elisabeth Bumiller New York Times article on this at length.

The conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan have cost Americans a staggering $1 trillion to date, second only in inflation-adjusted dollars to the $4 trillion price tag for World War II, when the United States put 16 million men and women into uniform and fought on three continents. (27)

But while the numbers are high in absolute terms, a second look

shows another story underneath. In 2008, the peak year so far of war spending for Iraq and Afghanistan, the costs amounted to only 1.2 percent of America’s gross domestic product. During the peak year of spending on World War II, 1945, the costs came to nearly 36 percent of G.D.P. (28)

With the cost of the war being eminently affordable, there’s little burden on US citizens.

“The army is at war, but the country is not,” said David M. Kennedy, the Stanford University historian. “We have managed to create and field an armed force that can engage in very, very lethal warfare without the society in whose name it fights breaking a sweat.” The result, he said, is “a moral hazard for the political leadership to resort to force in the knowledge that civil society will not be deeply disturbed.” (29)

The wars haven’t imposed a painful tax burden either. Bumiller points out that,

taxes have not been raised to pay for Iraq and Afghanistan — the first time that has happened in an American war since the Revolution, when there was not yet a country to impose them. Rightly or wrongly, that has further cut American civilians off from the two wars on the opposite side of the world. (30)

Some will say the anti-war movement is weak because it has been hijacked by the Democrats and derailed by Obama’s beguiling anti-war rhetoric. While these factors can’t be discounted, it seems more likely that a greater cause of the weakness can be found in the light to virtually non-existent costs the wars have imposed on the civilian populations of the aggressor countries and the failure of massive demonstrations of the past to make any difference, coupled with the expectation that future demonstrations will likewise fail to influence decision-makers. People seem to implicitly recognize that on matters of foreign affairs, governments operate on a plane completely divorced from, and unresponsive to, public opinion expressed in peaceful, respectful, and non-disruptive ways. Or to put it another way, despite its vaunted status, democracy, as it is practiced in most places, bears little connection to the original and substantive meaning of the word.

Questions

Everything about Bush’s wars, now Obama’s wars, and which have always been US wars and more broadly wars for profits, is false. They weren’t started to reduce threats to the physical safety of citizens of the countries that waged them, but to consolidate US domination of the Middle East to ensure the region’s land, labor, markets and especially its raw materials and petro-resources are available for the enrichment of the business enterprises of the United States and its allies. The effect has been quite the opposite of the stated intent. Rather than reducing the threat of terrorist attacks, which had arisen in response to ongoing US efforts to dominate the Middle East, the wars have increased the threat. Still, while the threat has increased, disruptions due to terrorist attacks have been minimal. The wars have made little difference in the lives of the citizens of the aggressor countries. As a result, while military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq are completely illegitimate and their continuation is opposed by majorities in the NATO bloc, they are not total wars involving global conflicts among fairly evenly matched countries that disrupt the lives of the citizens of all belligerents, but grossly uneven contests between an alliance of rich countries led by a global hegemon of unprecedented military power against weak, Third World, countries that suffer complete devastation while the civilian populations of the other side emerge unscathed. The gross imbalance in wealth and military strength means that for the hegemonic powers there is no need to inconvenience their civilian populations with conscription, there are no tax increases explicitly levied to fund the wars, and there are few retaliatory attacks of consequence. Civil society, accordingly, remains quiescent, and while its members may be morally and intellectually opposed to the wars, the costs they face as a result of the wars are too mild and the threat of jail and trouble with the police that an effective resistance implies is too great, to allow a strong, effective and sustained anti-war movement to develop. It seems that so long as disruptions are kept to a minimum and most people’s lives are kept fairly comfortable and filled with family, friends and work, that naked imperialism and rule by governments with utter disdain for popular opinion are possible as the normal features of political life in an imperialist “democracy”.

Contrast the quietude of life in the aggressor countries with conditions in Iraq (little different from those in Afghanistan.)

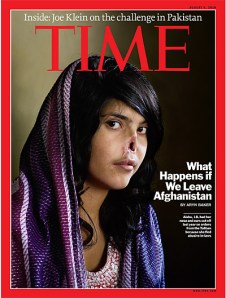

It’s not only the hundreds of thousands of dead and 4 million refugees. After seven years of US (and British) occupation, tens of thousands are still tortured and imprisoned without trial, health and education has dramatically deteriorated, the position of women has gone horrifically backwards, trade unions are effectively banned, Baghdad is divided by 1,500 checkpoints and blast walls, electricity supplies have all but broken down and people pay with their lives for speaking out. (31)

And what was the reason for producing this humanitarian catastrophe? It wasn’t to eliminate the threat posed by Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction, for Iraq’s WMDs would have posed little threat, if they existed, which they didn’t, when US and British troops invaded. Nor was it to eliminate a dictator. If it was, the costs — hundreds of thousands dead, four million refugees, and a destroyed society – can hardly be justified to eliminate a single man whose threat to the wider world was virtually nil. Neither was the reason for the 2003 invasion to guarantee access to the world’s energy supply so that Americans can continue to burn fossil fuels in their SUVs, run their power plants, keep their B2 bombers in the air, and continue to enjoy a standard of living based largely on petroleum. Yes, it’s true that the US standard of living depends on oil, but the United States is capable of satisfying its energy requirements through ready access to plentiful supplies of oil located elsewhere in the world and closer to home. Its next door neighbour, Canada — which is a virtual appendage of the United States — has the world’s largest reserves of oil after Saudi Arabia. No, the reasons for the invasion of Iraq weren’t WMDs, eliminating a dictator, and keeping the world’s oil supply out of the hands of radicals and extremists; the reason was to secure a bonanza of profits for US oil majors from the sale of Iraqi oil to Western Europe and Japan, the principal customers for oil from the Middle East. Energy profits – specifically those to be derived from transforming Afghanistan into “a conduit and a hub between South and Central Asia so that energy can flow to the south” – figured in the decision to invade that country. In a business society where key decision-making posts in the state are filled by corporate executives, corporate lawyers and ambitious politicians backed by corporate money, is it really any surprise that its wars, much as almost everything else about it, are organized around the inexorable need of business to expand its capital?

All of this should leave us thinking about how much substance there is to the idea that we live in democracies of the many; of whether the democracies we live in are really democracies of, for, and by the few; and whose interests really matter. Other questions: How can the societies in which we live be made different? Who – and what — is standing in the way of real, meaningful change? And how might the roadblocks be swept away? Also: What conditions conduce to the mobilization of the mass energy necessary to bring about radical change? And what activities carried out when the conditions are not present can facilitate their emergence and prepare for the time they do emerge?

1. “Iraq surveys show ‘humanitarian emergency’”, UNICEF.org, August 12, 1999. http://www.unicef.org/newsline/99pr29.htm

2. Tim Arango, “War in Iraq defies U.S. timetable for end of combat”, The New York Times, July 2, 2010.

3. The New York Times, September 27, 2007.

4. Seumas Milne, “The US isn’t leaving Iraq, it’s rebranding the occupation”, The Guardian (UK), August 4, 2010.

5. Milne

6. Research Unit for Political Economy, Behind the Invasion of Iraq, Monthly Review Press, New York, 2003, pp. 97-98; Albert Szymanski, The Logic of Imperialism, Praeger, 1983, pp. 161-166.

7. David Harvey, The New Imperialism, Oxford University Press, 2003.

8. Robert A. Pape, “The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism”, American Political Science Review, Vol. 97, No.3, August 2003.

9. Pape.

10. Pape.

11. V.G. Kiernan, America: The New Imperialism, Verso, 2005, pp. 293.

12. William Blum, ”The Anti-Empire Report”, August 4, 2010, http://killinghope.org/bblum6/aer84.html

13. Elisabeth Bumiller, “The war: A trillion can be cheap”, The New York Times, July 24, 2010.

14. Peter Baker and Eric Schmitt, “Several Afghan strategies, none a clear choice,” The New York Times, October 1, 2009.

15. William Blum, “The Anti-Empire Report”, December 9, 2009.

16. Naomi Klein, “Big Oil’s Iraq deals are the greatest stick-up in history,” The Guardian (UK), July 4, 2008.

17. The Observer (UK), September 16, 2007.

18. The Guardian (Australia), September 5, 2007.

19. Research Unit for Political Economy.

20. Sarah Lyall, “Ex-official says Afghan and Iraq wars increased threats to Britain”, The New York Times, July 20, 2010.

21. Haroon Siddique, “Iraq inquiry: Saddam posed very limited threat to UK, ex-MI5 chief says”, The Guardian (UK), July 20, 2010.

22. Siddique.

23. In April 2010, 39 percent of Canadians supported Canada’s military mission to Afghanistan, while 56 percent opposed it. “Support for Afghanistan Mission Falls Markedly in Canada,” http://www.visioncritical.com/2010/04/support-for-afghanistan-mission-falls-markedly-in-canada/

Two out of three Germans are opposed to the war, according to a poll in Stern magazine. Judy Dempsey, “Merkel tries to beat back opposition to Afghanistan”, The New York Times, April 22, 2010.

Some 72 per cent of Britons want their troops out of Afghanistan immediately. William Dalrymple, “Why the Taliban is winning in Afghanistan”, New Statesman, June 22, 2010.

In the United States, public opinion polls show that a majority of Americans have turned against the war. Dexter Filkens, “Petraeus takes command of Afghan mission”, The New York Times, July 4, 2010.

A July 11 ABC/Washington Post poll, found just 42 percent of respondents said that the Afghan War was “worth fighting” — with a majority, 55 percent, saying they did not think it was. A CNN poll (5/29/10) found that 56 percent opposed the war in Afghanistan, while 42 percent supported it. In three surveys since July, the AP/GfKpoll has reported that at least 53 percent of respondents say they oppose the Afghanistan War. In September, 51 percent told the Washington Post/ABC News poll (9/10–12/09) that the war was not “worth fighting.”

Steve Rendall, “USA Today: Americans continue to support Afghan war—in 2001”, FAIR Blog, July 30, 2010.

24. Arango.

25. Kiernan, p.302.

26. Kiernan, pp. 340-341.

27. Bumiller.

28. Bumiller.

29. Bumiller.

30. Bumiller.

31. Milne.