By Stephen Gowans

Gilbert Achcar hates Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi. That much is clear from Achcar’s three Z-Net articles, the latest published on April 23, in which the Lebanese socialist and sometimes “anti-war activist” urges the left to support the rebel uprising in Libya and not to oppose the NATO-enforced no-fly zone. In his latest article, which amounts to a defense of his position against the firestorm of criticism he has drawn for urging the left not to oppose Western military intervention in Libya, Achcar denounces Gaddafi as a psychopath. By demonizing Gaddafi, Achcar acts to legitimize the Benghazi rebellion and therefore Western support of it. There are likely to be more than a few psychopaths among the rebels. And applying Achcar’s amateur political psychography, we could probably denounce the Saudi monarchy, which has brutally suppressed the rebellion in Bahrain, as being as rife with psychopaths as Libya’s leadership. But Achcar appears to be more agitated by the Libyan psychopaths than the Saudi, Bahraini, Israeli, or indeed, even US, British and French ones. Politics based on the presumed psychological failings or mental states of leaders is illegitimate, and no genuine socialist, at least no Marxist one, practices it.

On top of demonizing Gaddafi, Achcar tries to make the rebels more palatable than they are. The rebellion, Achcar assures us, is made up of “the same mix of political forces that are active in most other uprisings in North Africa and the Middle East, i.e., liberal democrats, various types of Islamic currents from moderate to extreme, former members of the regime…and left-oriented groups and persons.” Doubtlessly, some “left-oriented groups and persons” count themselves among the Libyan rebels, but there is no evidence that their numbers are large and that they have any influence within the insurrection. Even Achcar questions whether the left has a significant presence. In a footnote, he writes: “The last time there was any indication about an organized left in Libya, to my knowledge, was in the early 1970s when news came out about the repression of a Trotskyist group there.”

One of the less palatable elements of the rebellion, whose presence Achcar does acknowledge, are radical Islamists, about whom evidence is growing that they are playing key roles in the revolt. Rod Nordland and Scott Shane, writing in the New York Times of April 24, 2011 (1) profile Abu Safian Ibrahim Ahmed Hamuda bin Qurnu, a “tank driver in the Libyan Army in the 1980s” who joined Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan in the early 1990s, was incarcerated by the United States at Guantanamo after September 11, 2011, released to Libya in 2007, and has since become “a notable figure in the Libyan rebels’ fight to oust” Gaddafi. He leads the Darnah Brigade, named after a port town in northeast Libya which “has a long history of Islamic militancy, including a revolt against Colonel Gaddafi’s rule led by Islamists in the mid-1990s.” “Activists from here,” note Nordland and Shane, “are credited with starting the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group.”

Last week, Ottawa Citizen reporter David Pugliese obtained Canadian military documents which reveal that Canada’s Department of National Defence considers the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group to be a terrorist group associated with al-Qaeda. (2) The US State Department has also designated the group as a terrorist organization, a point Nordland and Shane might have made, considering the group plays an important role in the rebellion against Gaddafi. The organization was set up in Afghanistan in the early 1990s, and “had tried to assassinate Gaddafi on several occasions.” Gaddafi perceives the group to be “a mortal enemy.” Abdel-Moneim Mokhtar, “a leading member of the NATO backed rebels,” according to Pugliese, “had also been a top commander in the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group.” And according to the Combatting Terrorism Center at West Point, 52 of 440 suicide bombers in Iraq were from the group’s hometown of Darnah. (3) These are not leftists or even liberal democrats trying to bring about a more progressive alternative to Gaddafi.

Quoting Pugliese at length:

A Canadian intelligence report written in late 2009 also described the anti-Gadhafi stronghold of eastern Libya as an “epicentre of Islamist extremism” and said “extremist cells” operated in the region. That is the region now being defended by a Canadian-led NATO coalition.

The report by the government’s Integrated Threat Assessment Centre said “several Islamist insurgent groups” were based in eastern Libya and mosques in Benghazi were urging followers to fight in Iraq.

But extremists operating in eastern Libya were not the only forces Gadhafi had to deal with.

DND’s report notes that in 2004 Libyan troops found a training camp in the country’s southern desert that had been used by an Algerian terrorist group that would later change its name to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb or AQIM.

That group was behind the 2008 kidnapping of Canadian diplomats Robert Fowler and Louis Guay.

Still other reports have come to light about Islamic extremists in rebel ranks. The Wall Street Journal reported that Sufyan Ben Qumu, a Libyan army veteran who worked for Osama bin Laden’s holding company in Sudan and later for an al-Qaeda-linked charity in Afghanistan, is training rebel recruits.

He spent six years at the U.S. prison in Guantanamo Bay.

Abdel Hakim al-Hasady, an influential Islamic preacher who spent five years at a training camp in eastern Afghanistan, also oversees recruitment and training for some rebels. (4)

I daresay it would be easy enough to decry radical Islamists as psychopaths, though it’s interesting that Achcar reserves this obloquy for Gaddafi, and prefers to attach a non-emotional descriptive label to the al-Qaeda-associated rebels. In Achcar’s hands, whereas Gaddafi is a psychopath, the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group is nothing more than an Islamic current. It’s unlikely that the aims of the Islamists in seeking the overthrow of Gaddafi have much to do with establishing a liberal democracy, let alone socialism. Nevertheless, Achcar urges the left to back their rebellion.

Taking care to keep other less savory elements of the Benghazi rebel force from complicating his call for left support for the rebels, Achcar omits to mention that royalists make up a significant part of the mix of political forces seeking Gaddafi’s ouster, as do people with key connections to the US state, who have managed to secure important roles in the insurrection. These include:

• Khalifa Heftir, a former Libyan Army colonel, who spent the last 25 years living seven miles from CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia with no obvious means of support. (5) Heftir says “he had often talked to the Central Intelligence Agency while he lived in exile in suburban Virginia.” (6) He is one of, if not the rebels’, top military leader.

• Mahmoud Jibril “earned his PhD in 1985 from the University of Pittsburgh under the late Richard Cottam, a former US intelligence official in Iran who became a renowned political scientist specializing in the Middle East.” Jibril “spent years working with Gaddafi’s son Saif on political and economic reforms … (b)ut after hardliners in the regime stifled the reforms, Jibril quit in frustration and left Libya about a year ago.” (7) Jibril has been out of Libya since the uprising began, meeting with foreign leaders. (8)

• Ali Tarhouni, the rebel government’s finance minister, had been in exile for the last 35 years. His latest job was teaching economics at the University of Washington.

Achcar’s description of the rebels as a mix of political forces from liberal democrats to left-oriented groups hardly seems to accord with the reality that (a) there is no evidence that the left plays a significant role in the rebellion, and that (b) the largest part of the rebel mix is comprised of al-Qaeda-connected radical Islamists, royalists, and political and military leaders linked to the US intelligence community. There may be some ambiguity about how left Gaddafi is, and far less about his anti-imperialism, but whatever ambiguity there is about Gaddafi’s political position, there is certainly none about how left the rebels are. They aren’t.

Achcar’s Position

Achcar’s position amounts to this: Gaddafi is a demon; his ouster, therefore, is welcome; whatever comes after Gaddafi must be better than Gaddafi; the left shouldn’t support the NATO no-fly zone, but nor should it oppose it; this position would have raised the Western left’s credibility among left forces in North Africa and Western Asia; the left should now pressure Western governments to arm the rebels.

Let’s consider each point in turn.

Gaddafi is a demon.

Demonization is a hoary practice that governments have long used to mobilize support for war, and which anyone on the left should be on guard against. In addition to being used by imperialist governments to drum up support for war and other interventions, demonization is also often used by left writers associated with Z-Net and the Campaign for Peace and Democracy, and was used, too, by many members of the Second International to support their own countries’ participation in WWI. [Plekhanov, the father of Russian Marxism, became a fervent supporter of freedom and democracy against despotism and militarism when war clouds rolled in, despite agreeing before the war to mount a principled opposition to it should it come.] As shown by Achcar’s readiness to denounce Gaddafi as a “psychopath,” these writers have become as zealous as the State Department and major media, if not more so, in branding targets of Washington’s imperial designs as demons. This, unfortunately, happens during every major mobilization of Western diplomatic, intelligence and military forces against non-satellite countries. Left politics should not be based on legitimizing the pretexts for war of imperialist governments, nor on the alleged failings or virtues of leaders. They should be based on an analysis of class forces.

“If I were not old and sick I would join the army,” declared Plekhanov. “To bayonet our German comrades would give me great pleasure.” (9) Achcar expressed horror at the prospect of loyalist forces perpetrating a bloodbath in Benghazi, and in his first article in the series called for the left not to oppose a NATO no-fly zone on the grounds that it was the only way to avert a bloodbath. But his horror at bloodletting doesn’t seem to extend to that which promises to be brought about by the rebels, who he urges Western governments to arm. Hence, despite raising fears about a bloodbath, avoidance of bloodshed really doesn’t seem to weigh heavily in Achcar’s considerations. He doesn’t mention the efforts of the African Union to bring about a cease-fire or urge that the left support it. He’s silent on Gaddafi’s acceptance of the AU proposal and on the rebels’ rejection of it. It would appear, then, that it is not avoiding bloodbaths that galvanizes Achcar so much as avoiding the defeat of the rebels. One suspects that, as was true of Plekhanov, to bayonet our comrades on the other side would give Achcar great pleasure.

Whatever comes after Gaddafi must be better than Gaddafi.

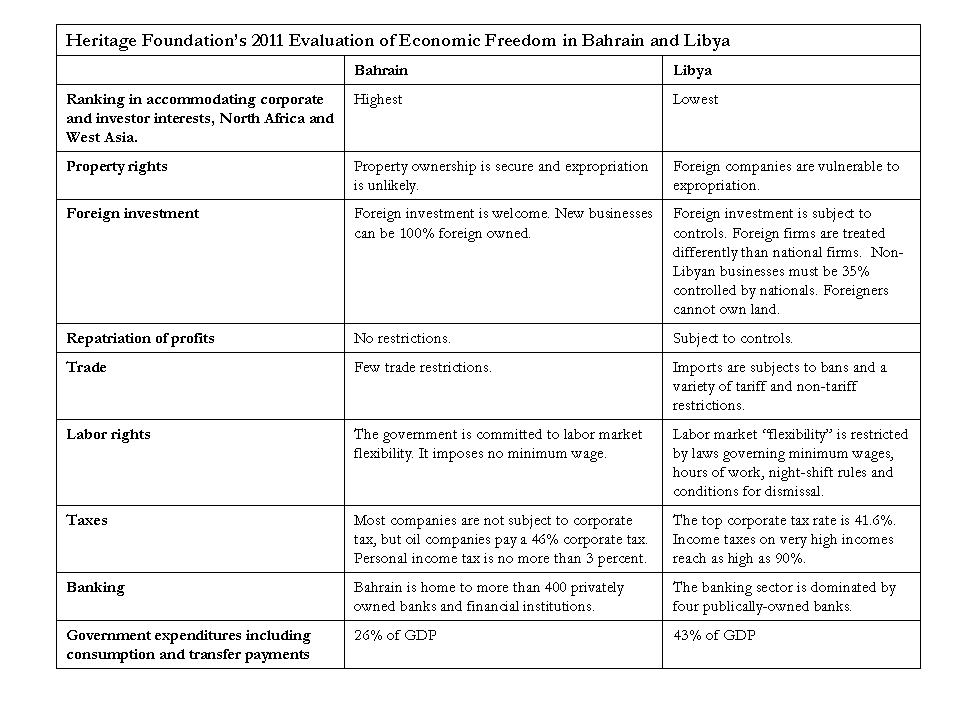

In the lead up to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, some left writers insisted the world—and Iraq– would be a better place without Saddam Hussein. It’s one thing to say Hussein was hardly a heroic figure and that he had blood on his hands, but quite another to brand him as so vile that nothing could be worse, as many left writers did. It should have, however, been clear that Iraq would be no better off under a US occupation—and would probably be substantially worse off, and indeed, this prediction has been borne out. Likewise, Gaddafi’s ouster will not be followed by a liberal democracy, much less socialism, but likely a new neo-colonial arrangement, in which Libya becomes an impoverished satellite of the West, as Serbia and Iraq have become. The idea that the Libyan rebels either want to, or are in a position to bring about, a progressive alternative to Gaddafi is pure fantasy. In order for this to happen, an organized political left would need to exist in Libya that was capable of mobilizing popular support, not against the current regime alone, but also for a qualitatively different regime that is either fiercely hostile to being placed in chains by outside forces, represents the interests of the mass of people, or both. But there is, by Achcar’s own admission, no such left political force in the country. The best the rebels can do is force Gaddafi’s ouster, but it is very likely that his successor, will, as was true in Serbia and Iraq, lead a neo-colonial puppet regime. For all its failings and recent willingness to cooperate with the West, the Gaddafi government has not gone so far as to integrate Libya’s land, labor and resources unconditionally into the global economy and has a history of acting for the benefit of its own people—which enjoys the highest standard of living in Africa. That it hasn’t unconditionally catered to the profit-making interests of foreign corporations and investors is the reason why Washington has long been hostile to the Gaddafi government, and explains its willingness to assist an armed rebellion to overthrow Gaddafi, while taking no such steps to aid a peaceful rebellion to throw off the weight of the Khalifa despotism in Bahrain, which runs its country as an annex to the United States, letting the US Fifth Fleet operate from there, while maintaining a low-tax, worker-unfriendly, foreign-investment friendly regime.

The left shouldn’t support the NATO no-fly zone, but nor should it oppose it.

What Achcar is really saying is that the left should line up with the rebellion in Libya, but not with Washington and not with Tripoli. Thus, supporting the rebels means not opposing their call for a no-fly zone. But at the same time, the left shouldn’t support the no-fly zone, because that would mean it supports NATO. This is the Campaign for Peace and Democracy’s fence-straddling approach. In the 1980s, it was manifest in the position of: We’re not for Washington and we’re not for the Polish government, but we are for the Solidarity trade union. The validity of this approach, however, depends on the question of whether the rebels ought to be supported, just as in the 1980s it depended on the question of whether the left should have thrown in its lot with the Wall Street Journal, the CIA, Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan in supporting Solidarity. Solidarity, it turned out, wasn’t the harbinger of the kind of socialism it was safe to discuss at the dinner table that the CPD and other leftist groups naively thought it would be. On the contrary, it was the nucleus for a neo-liberal make-over of Poland as a dependent US satellite – what’s likely to be in store for Libya if the rebels prevail.

The key questions are: Who are the rebels? What are their goals? Who is the government? What are its goals? Achcar’s answers seem to be: The government is led by a psychopath who has an insatiable hunger for power which drives him to extremes of violence. (In the 1980s: the Polish government is communist and hungry for power.) The rebels are against this, and therefore, must be worthy of support. (Solidarity is against the government and therefore must be worthy of support.) But this line of reasoning is no different from the logical blunder of assuming the enemy of my enemy is my friend, a blunder that anti-imperialists are routinely accused of making. It doesn’t follow that rebels are worthy of support simply because they’re rebels or simply because they’re rebelling against a government led by someone you don’t like.

This position would have raised the Western left’s credibility among left forces in North Africa and Western Asia.

Many members of the Second International argued that they had to vote for war credits otherwise they would have lost credibility with their base which had become infected by pro-war chauvinism. Failing to support their own governments in war would mean losing influence with a jingoism-besotted working class for decades to come. Lenin, who Achcar has portrayed as a compromiser who would have gladly accepted a NATO no-fly zone, and who did indeed make compromises where necessary, was doctrinaire, just as much as he was willing to make necessary compromises; which is to say, he was unwilling to yield on principle for short-term gain, but would yield, if he had to, to safeguard fundamental positions. In the debates about whether to tear up their agreements to withhold support for their governments in war, Lenin stood out among socialist leaders, arguing that the leaders’ role was to lead, not to follow. Refusing to oppose the no-fly zone as a means of gaining influence with left organizations in Western Asia and North Africa that called for one, reverses the roles of influence and principle. The point isn’t to abandon principle to gain influence, but to use influence to advance principle.

The left should now pressure Western governments to arm the rebels.

The idea that pressure from the left will persuade Western governments to arm the rebels, who will then pursue their rebellion free from Western control, is pure fantasy. The left exerts approximately zero influence on Western foreign policy, and even if it exerted more, on a matter as fundamental as this to the geostrategic interests of Western governments, it would be ignored. Western governments won’t arm rebel groups they can’t control and which are working toward objectives they don’t share. Achcar may as well say the left’s position ought to be to pressure Washington, London and Paris, to introduce ground forces into Libya to sweep Gaddafi from power and to install a new Marxist government.

Conclusion

Achcar has added nothing new in his third attempt to drum up left support for the Libyan rebels, apart from ratcheting up the demonization of Gaddafi by calling him a psychopath, a dubious practice favored by Western governments and major media, and which shouldn’t be the basis of the political positions of the left. Gaddafi may indeed be a psychopath, but so too may be many other leaders, including those who have key roles in the Libyan insurrection. It’s doubtful that Achcar would surrender his support for the rebels, if it were revealed that its leaders were psychopaths, or if they were to drench Gaddafi’s supporters in blood. Whether Gaddafi is or isn’t a psychopath is unclear, but more importantly, is irrelevant. What is relevant to a discussion of what position the left ought to take is class analysis, none of which Achcar provides. Instead, the Z-Net favorite leans toward the rogues’ gallery view of left politics, a kind of up-to-date left version of the great man theory of history, where monsters, psychopaths and thugs—and the US governments that fight them– have replaced great men as the fundamental agents of history. The practice that depends on this theory is to visibly demonize the leaders the US State Department brands as thugs, despots, and dictators, while saying little about the thugs, despots, and dictators the State Department doesn’t want to talk about (like the Saudis, Israelis, and Egypt’s military rulers.) Achcar may denounce all of these from time to time, but he hasn’t written a series of articles urging the left to pressure Western governments to arm the Palestinians against the Israelis and nor Egyptian or Bahraini rebels against their governments.

Achcar also seeks to demonize those who have criticized his position in what he considers to be less than a comradely way by suggesting that, were they in power, they would have had him sent to the gulag. Were Achcar in power, would he send Gaddafi and his supporters to that modern Western gulag, the ICC? Whether any of his critics would banish Achcar to the gulag is unclear, but that he brings it up seems in keeping with his preference for building political positions around demonization, fantasy and conjecture. It is a fantasy that left pressure will compel Western governments to arm the rebels; a fantasy that even were this true that Western governments would arm the rebels unconditionally; a fantasy that with Western fingers in the Libyan pie that Gaddafi’s ouster will be succeeded by a more progressive alternative; and a fantasy that liberal democrats and left-oriented groups and persons preponderate the royalists, al-Qaeda connected terrorists and suicide bombers, and US intelligence community-linked political and military leaders in the rebel ranks.

Finally, it is a fantasy to think that no one sees through Achcar’s I-don’t-support-Western-military-intervention-but-neither-do-I-oppose-it position as the dissembling of a coward who has convinced himself that he has brilliantly finessed the problem of how to support the rebels without looking like he’s also supporting their imperialist backers. This is the kind of dishonest double-talk that one normally expects from unctuous politicians, not socialist anti-war activists. As he has doubtlessly discovered, judging by the firestorm of criticism he’s called upon himself, his no-fly zone position just doesn’t fly. All that Achcar has succeeded in doing in championing the case on three occasions for the left to back the Libyan rebels is to demonstrate that he is neither anti-war nor anti-imperialist nor particularly adverse to bloodbaths. Maybe he shouldn’t be sent to the gulag, but he should certainly be sent to the corner, along with every other socialist who seeks to enlist the left in the support of its own governments in pursuit of their own bourgeoisies’ interests.

1. Rod Nordland and Scott Shane, “Libyan shifts from detainee to rebel, and U.S. ally of sorts”, The New York Times, April 24, 2011.

2. David Pugliese, “DND report reveals Canada’s ties with Gadhafi”, The Ottawa Citizen, April 23, 2011.

3. Nordland and Shane.

4. Pugliese.

5. “Professor: In Libya, a civil war, not uprising”, NPR, April 2, 2011. http://www.npr.org/2011/04/02/135072664/professor-in-libya-a-civil-war-not-uprising

6. Rod Nordland, “As British help Libyan rebels, aid goes to a divided force”, The New York Times, April 19, 2011.

7. Farah Stockman, “Libyan reformer new face of rebellion”, The Boston Globe, March 28, 2011.

8. Kareem Fahim, “Rebel leadership in Libya shows strain”, The New York Times, April 3, 2011.

9. Neil Harding. Lenin’s Political Thought: Theory and Practice in the Democratic and Socialist Revolutions. Volume II, Haymarket Books. 1978. P. 12.