January 21, 2022

By Stephen Gowans

Joe Biden thinks, or at least says he thinks, that a Russian invasion of Ukraine would “be the most consequential thing that’s happened in the world in terms of war and peace since World War II.” Biden is either delusional, or supremely confident in the power of US propaganda to turn black to white, otherwise he couldn’t possibly summon the chutzpah to utter such arrant nonsense. Unless Russia plans (a) to invade Ukraine and then (b) burn it to the ground, as the United States did to North Korea from 1950 to 1953, or napalm and exfoliate the country, as Washington did to Vietnam, or bomb and sanction it into the stone age, as the Pentagon did to Iraq twice, or spend 20 years killing civilians in drone strikes as four US administrations did to Afghanistan, then Russia could hardly match the United States in producing consequential markers on the record of post-World War II war and peace.

Equally absurd are the remarks of the leader of one of Washington’s favorite lickspittles, the government of Canada. “We are working with our international partners and colleagues to make it very, very clear that Russian aggression is absolutely unacceptable,” intoned the popinjay Justin Trudeau, a man whose servility to US interests is without limit. “We are standing there with diplomatic responses, with sanctions, with a full court press to ensure Russia respects the people of Ukraine.” Too bad Canada hadn’t acted to ensure the United States respected the peoples of Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, Iraq, and Afghanistan, to say nothing of the peoples of Iran, Cuba, Venezuela, and Palestine, among others.

To avoid the terrible fate of being excommunicated from the church of respectable bourgeois politics, Canada’s peace and love party, the NDP, advocated the use of “sanctions” rather than “war” to deter what is said by governments and respectable (i.e., bourgeois) media in the West to be an anticipated Russian “aggression” against Ukraine, thus accepting as legitimate and propagating two spurious claims: (1) that sanctions—which regularly produce death and misery in excess of what is wrought by bullets, shells, bombs, and missiles—are a peaceful and desirable alternative to war, rather than a means of warfare itself, and a particularly vicious one at that; and that (2) Russian aggression lies at the heart of the dispute over Ukraine.

At its base, the conflict between Russia and the United States pivots on the question of security guarantees. Russia has asked for them and the United States refuses to grant them. Why does Russia feel insecure?

For one thing, the country, along with China, is at the center of the US reticle—Russia constituting what Washington calls a “revisionist power.” “Revisionist”, in US hands, means seeking to revise the international rules-based order—an order based on a set of shifting rules of which the United States alone is the architect and which it invokes whenever convenient, for its own benefit. Revising the international order is refusing to do whatever the US commands. The US president, uncrowned king of the world, or much of it, might as well intone, “The international rules-based order, c’est moi.” US politicians and journalists are quick to use the words “dictator” and “authoritarian” to refer to the targets of US aggression, but, skilled propagandists to a person, refuse to use the words in reference to Washington’s own relationship with the rest of the world. Yet the words fit to a tee. The United States seeks a relationship of prepotency vis-à-vis other countries. Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger described the relationship this way, in an amusing 1970s song, sung to the tune Yankee Doodle.

Yankee Doodle came to town

H-bombs in his pocket

Says chum if you don’t toe the line

I’ll blast you with my rockets

To be sure, the dictator’s tools of coercion have always surpassed H-bombs alone and include sanctions (more aptly known as starving people into submission, a favorite of Canada’s “peace-loving” NDP), fomenting rebellions, and declaring US toadies to be the legitimate leaders of countries that defy the US dictatorship (Juan Guaidó, for example.)

In 2019, the RAND Corporation, the Pentagon’s think tank, drew up a list of measures the United States and its satellites, such as henchman Canada, could take to “overextend and unbalance” Russia as a means of coercing Moscow to toe the US line. The measures were:

- Expand U.S. energy production to stress Russia’s economy, potentially constraining its government budget and, by extension, its defense spending. By adopting policies that expand world supply and depress global prices, the United States can limit Russian revenue.

- Increase Europe’s ability to import gas from suppliers other than Russia to economically extend Russia.

- Impose deeper trade and financial sanctions to degrade the Russian economy.

- Challenge the legitimacy of the state. Create the perception that Moscow is not pursuing the public interest by focussing on widespread, large-scale corruption.

- Encourage domestic protests and other nonviolent resistance to distract or destabilize the Russian government.

- Undermine Russia’s image abroad to diminish Moscow’s standing, influence and prestige.

- Encourage the emigration from Russia of skilled labor and well-educated youth.

- Relocate bombers and missiles within easy striking range of key Russian strategic targets to raise Russian anxieties.

The point is that the United States views Russia as a challenge to what the late Hugo Chavez once called the international dictatorship of the United States and Washington has not allowed the challenge to its dictatorship to stand.

The second reason for Russia to feel insecure, if the first isn’t enough, is that the United States is the world’s greatest menace to peace, contrary to the efforts of Joe Biden, Justin Trudeau, sanctions-loving social democrats, and the Western bourgeois media to flip this reality on its head. The United States’ addiction to war—according to Washington’s own Congressional Research Service, “the US military has waged war, engaged in combat, or otherwise employed its forces aggressively in foreign lands in all but eleven years of its existence”, that is, in more than 95 of every 100 years since 1783—is brushed aside. Twenty years in Afghanistan, the destruction of Iraq, the illegal occupation of Syria, the air war on Yugoslavia, the bombing of Panama and invasion of Grenada, wars on the peoples of Vietnam and Korea, to say nothing of wars of economic aggression on these and countless other countries—all these US aggressions are forgotten. Instead, we’re led to believe that, motivated by a desire to recover territory lost to the Russian empire, Vladimir Putin has asked for security guarantees he knows Washington cannot grant, and will use the denial of these guarantees as a pretext to invade Ukraine. Why the United States cannot guarantee Russia’s security, and why security guarantees are “non-starters”, is never explained. However, the undeniable US record of worshiping Mars is explanation enough: The United States cannot provide security guarantees, because the rules-based international order, of which the United States is the sole architect and its plutocrats the principal beneficiaries, depends on military threat and aggression as its ultima ratio. The alluring goal of integrating Russia into the US economy as a complement to, rather than as a rival of, corporate USA, offers too many lucrative profit-making opportunities for Washington to voluntarily surrender its program of anti-Russian military pressure.

Moscow has presented its request for security guarantees in the form of two proposed treaties, one with the United States and the other with the United States’ instrument, NATO. As far as I can tell, the details of the proposed treaties have never been presented in major US media, perhaps because they contradict the Western narrative of Russian belligerence.

Draft treaty with the United States:

- Russia and the US shall not use the territory of other countries to prepare or conduct attacks against the other;

- Neither party shall deploy short- or intermediate-range missiles abroad or in areas where these weapons could reach targets inside the other’s territory;

- The US shall not open military bases in the post-Soviet countries that are not already NATO members, use their military infrastructure, or develop military cooperation with these states;

- Neither party shall deploy nuclear weapons abroad, and any such weapons already deployed must be returned. Both parties shall eliminate any infrastructure for deploying nuclear weapons outside their own territories;

- Neither party shall conduct military exercises with scenarios involving the use of nuclear weapons; and,

- Neither party shall train military or civilian personnel from non-nuclear countries to use nuclear weapons.

Draft treaty with NATO.

- NATO shall not expand further east and must commit to excluding Ukrainian membership;

- NATO shall not deploy additional forces or arms outside the borders of its members as of May 1997 (before the alliance started admitting Eastern European countries);

- NATO shall not conduct any military activity in Ukraine, Eastern Europe, the South Caucasus, or Central Asia;

- Russia and NATO shall not deploy short- or intermediate-range missiles within range of each other’s territories;

- All parties shall refrain from conducting military actions above the brigade level which shall be confined to a border zone to be mutually agreed upon; and,

- Neither party shall regard the other as an adversary or create threats to the other, and all parties shall commit to settling disputes peacefully, refraining from the use of force.

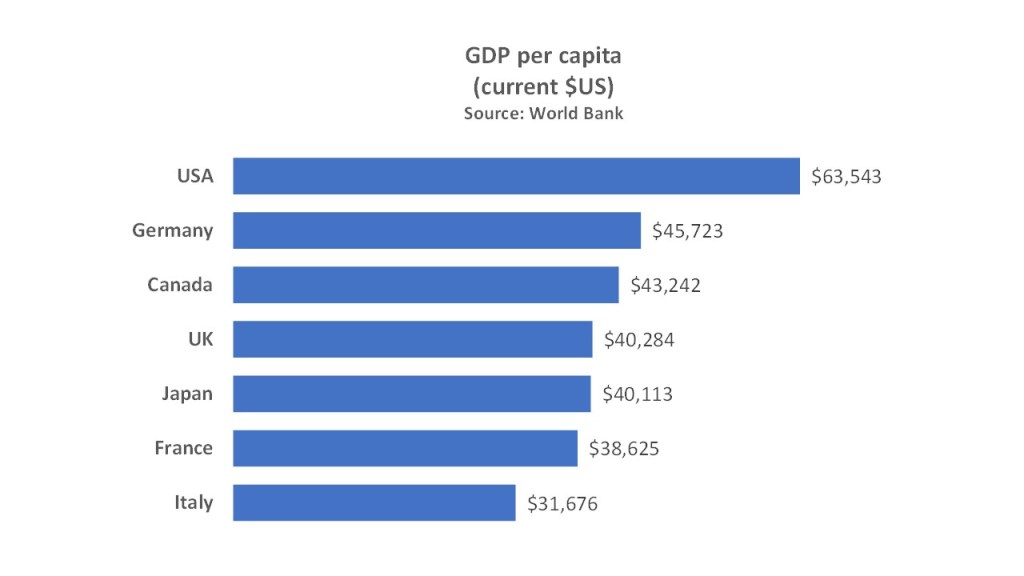

The provisions of the proposed treaties are in no way aggressive. On the other hand, the expansion of an anti-Russian military alliance up to the border of Russia, a country the alliance-leader, the United States, defines as a challenger to its hegemony, is unquestionably menacing to Russia. As to the canard that NATO cannot possibly pose a threat to Russia, for, after all, it’s merely a defensive alliance, that too depends on historical amnesia. An alliance that was at the center of unprovoked wars on Yugoslavia, Libya, and Afghanistan, is, ipso facto, an instrument of aggression. It is also an instrument of US domination, used (a) to keep Washington’s former imperialist rivals Germany, Britain, France, and Italy under US tutelage; (b) to create markets for US weapons manufacturers by demanding that NATO lackeys buy weapons systems that interoperate with the US military; and (c) to enlist NATO subalterns in the US project of “overextending and unbalancing” states that remain outside the US empire.

It may, contrary to what one reads in the press, be very much in the interest of Washington to provoke a Russian invasion of Ukraine. What better way to overextend and unbalance the Eurasian giant? A Russian invasion of the east European country would be a march into a quagmire. Washington welcomes the opportunity to overextend and unbalance Russia via a Ukrainian proxy—that is, to carry on the US war on Russia to the last Ukrainian. What’s more, and referring back to the RAND Corporation’s proposals, what better way than by provoking an invasion of Ukraine to do the following?

- Undermine Russia’s image abroad to diminish Moscow’s standing, influence and prestige.

- Create a justification to impose deeper trade and financial sanctions to degrade the Russian economy.

- Provide a pretext to relocate bombers and missiles within easy striking range of key Russian strategic targets to raise Russian anxieties.

- Pressure Germany to cancel Nord Stream 2 to increase Europe’s ability to import gas from suppliers other than Russia as a means of economically weakening Russia.

“Strobe Talbott, the original choreographer of NATO expansion in the post-cold war order,” as M.K. Bhadrakumar describes him, has “triumphantly congratulated Blinken and Jake Sullivan for cornering Russia.” And well he should. In Ukraine, Washington has created an anti-Russian state on Russia’s border, which, while not formally integrated in NATO, is a de facto NATO asset. Left alone, Ukraine poses a threat to Russia. Invaded by Russia, it remains equally a threat.

Provoking a robust Russian reply to an advancing and predatory NATO offers other benefits to Washington as well. France and Germany—the principal EU actors—evince a growing desire to achieve a strategic autonomy that would allow them to take advantage of the economic opportunities a closer relationship with Russia would create. Growing Russian-European economic integration would disadvantage US corporations. For example, in preference to reliance on Russian natural gas, Washington has pressed Europe to purchase liquid natural gas from the United States, even though the cost is much higher. Washington has also balked at the prospect of EU military autonomy on the grounds that it would cut US arms companies out of contracts for military provisioning. In other words, the United States uses its dominance over its former imperial rivals to tilt the field in favor of corporate USA (and also to keep former and therefore potential future imperialist rivals in check.) There’s a cost, then, of belonging to the US empire—sacrificing one’s own economic interests to those of the US plutocracy. A Russian invasion of Ukraine would provide Washington with a moral argument to pressure Germany and France into renouncing their growing openness to Russia in favor of more openness to corporate USA, while cementing Europe’s place in the US empire and countering the gravitational pull of Russia on European economies.

Russia is clearly threatened by the United States and its NATO alliance, and the treaties proposed by Russia to guarantee its security would desirably stay the hand of an aggressive Washington, to the benefit not only of Russia, but to those of us who live in NATO countries who have nothing to gain, and much to lose, from the US plutocracy’s continuing predatory advance on its rivals. Our enemies are the leaders of the column in whose ranks we are invited to march.

+++

Coming soon. The Killer’s Henchman: Capitalism and the Covid-19 Disaster. Available for pre-order from Baraka Books.